728x90

14 and cthe grace of our Lord overflowed for me with the dfaith and love that are in Christ Jesus. 15 The saying is etrustworthy and deserving of full acceptance, that Christ Jesus fcame into the world to save sinners, gof whom I am the foremost. 16 But I received mercy for this reason, that in me, as the foremost, Jesus Christ might display his perfect patience as an example to those who were to believe in him for eternal life. 17 To hthe King of the ages, iimmortal, jinvisible, kthe only God, lbe honor and glory forever and ever.4 Amen.

c Rom. 5:20

d [Luke 7:47, 50]; See 1 Thess. 1:3

e ch. 3:1; 4:9; 2 Tim. 2:11; Titus 3:8; [Rev. 22:6]

f Matt. 9:13; See John 3:17; Rom. 4:25

g [1 Cor. 15:9]

h [Ps. 10:16; Rev. 4:9, 10]

i ch. 6:15, 16; Rom. 1:23

j John 1:18; Col. 1:15; Heb. 11:27; 1 John 4:12

k Jude 25

l 1 Chr. 29:11

4 Greek to the ages of ages

The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2016), 딤전 1:14–17.

14 우리 주의 은혜가 그리스도 예수 안에 있는 믿음과 사랑과 함께 넘치도록 풍성하였도다

15 미쁘다 모든 사람이 받을 만한 이 말이여 그리스도 예수께서 죄인을 구원하시려고 세상에 임하셨다 하였도다 죄인 중에 내가 괴수니라

16 그러나 내가 긍휼을 입은 까닭은 예수 그리스도께서 내게 먼저 일체 오래 참으심을 보이사 후에 주를 믿어 영생 얻는 자들에게 본이 되게 하려 하심이라

17 영원하신 왕 곧 썩지 아니하고 보이지 아니하고 홀로 하나이신 하나님께 존귀와 영광이 영원무궁하도록 있을지어다 아멘

대한성서공회, 성경전서: 개역개정, 전자책. (서울시 서초구 남부순환로 2569: 대한성서공회, 1998), 딤전 1:14–17.

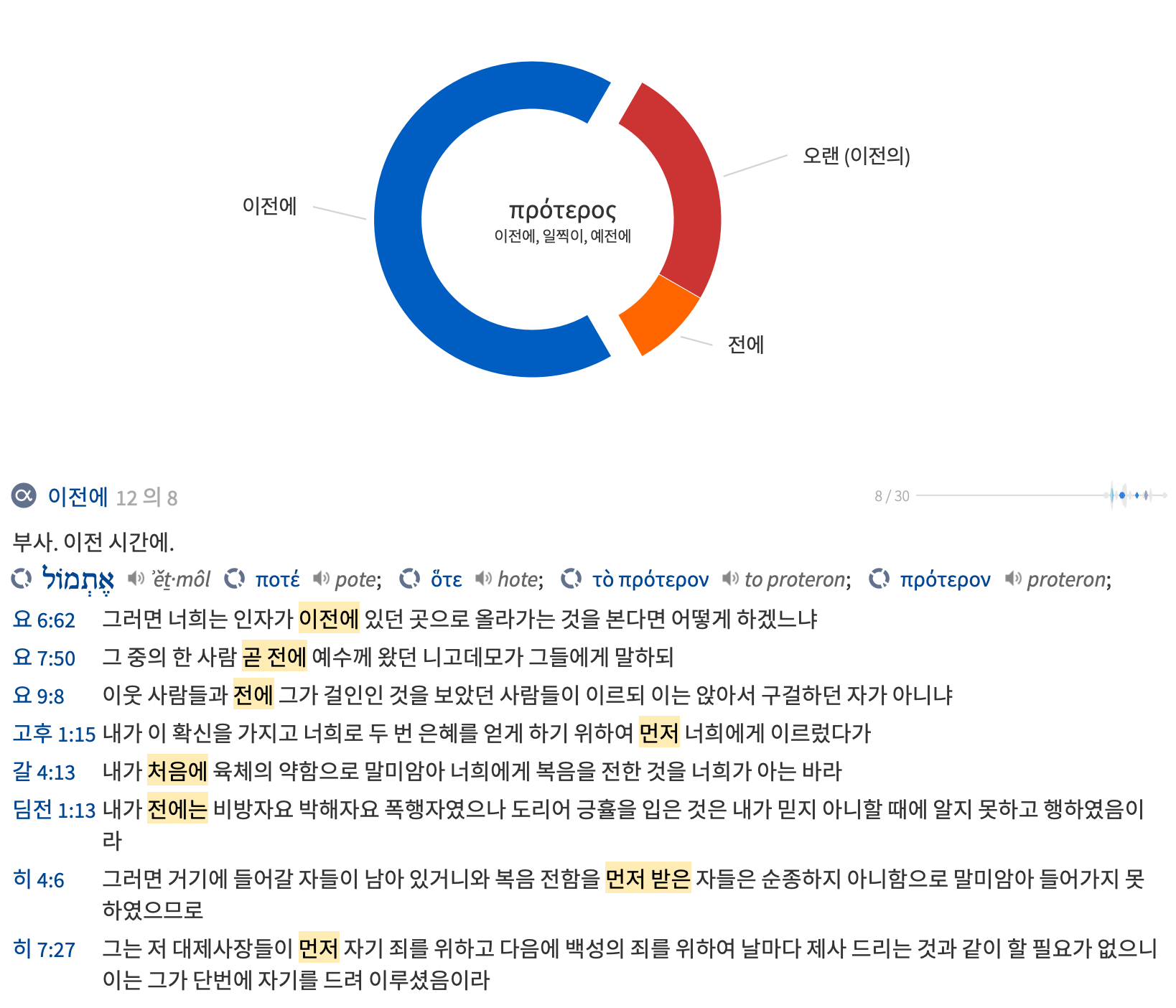

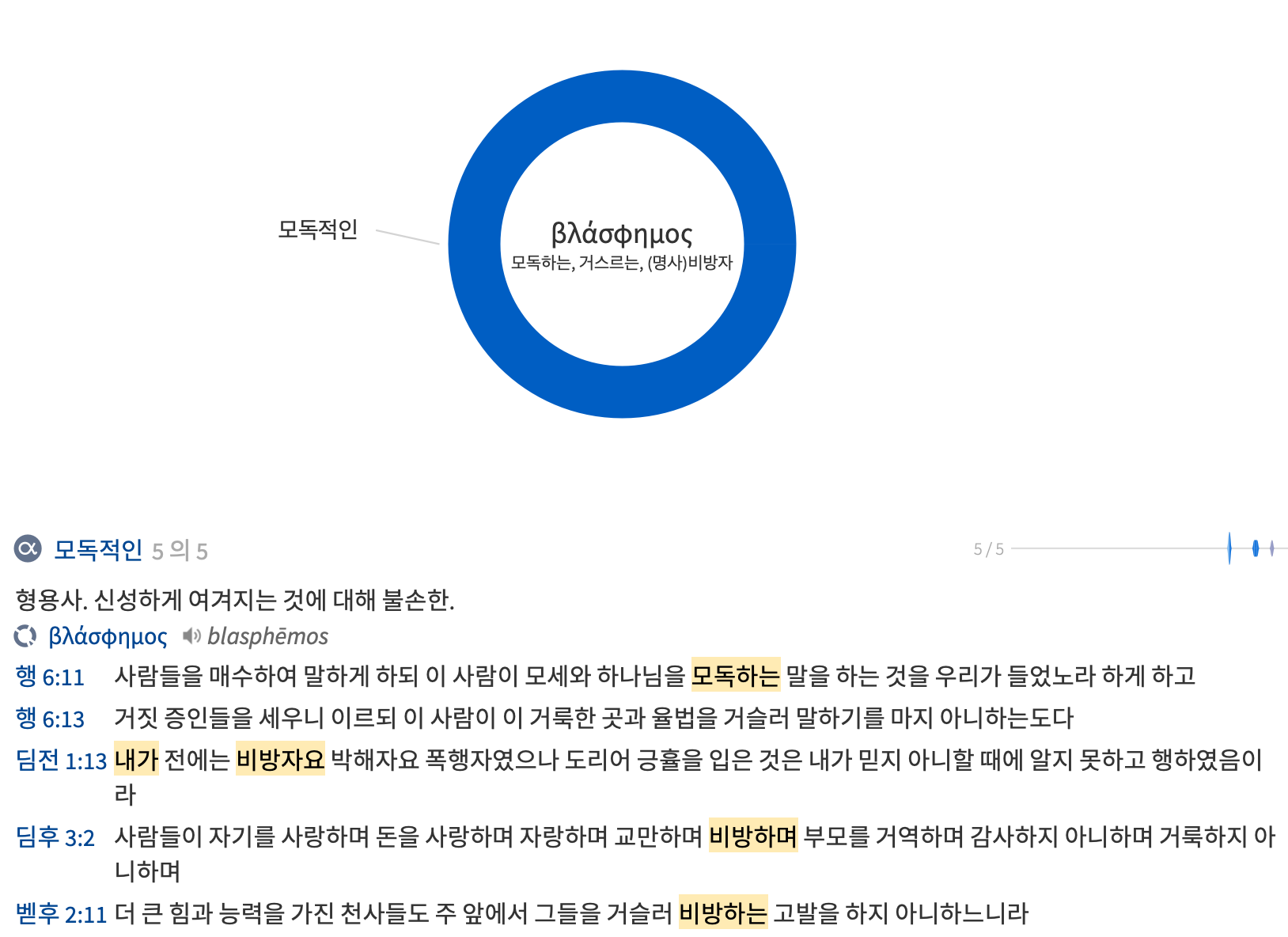

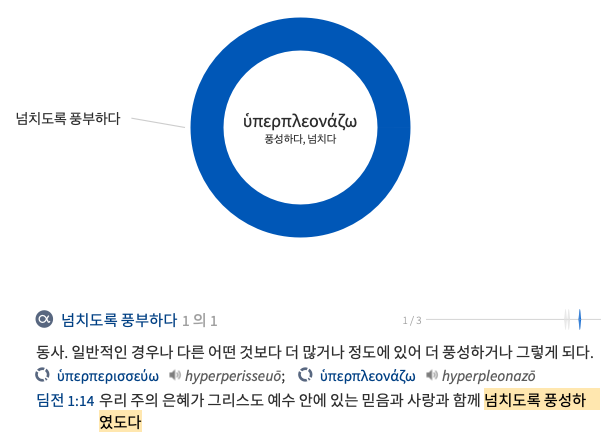

14절) ‘넘치도록 풍성하였도다’는 ‘휘페레플레오나센’으로 이것의 원형은 ‘휘페르플레오나조’이다. 이는 '~위에, ~을 넘어서'라는 의미의 전치사 ‘휘페르’와 ‘증가하다, 자라다’라는 뜻을 지닌 동사 ‘플레오나조’의 합성어로 ‘풍성하다, 넘치다’라는 의미이다. 이는 보통 혹은 일반적인 경우보다 훨씬 더 풍성한이라는 의미로 이곳에서 단한번 사용된 표현이다. 이전에 바울 자신이 비방자요 박해자요 폭행자였으나 주께서 그를 부르심으로 복음의 직분을 맡기신 것 그 자체로 자신에게 얼마나 큰 은혜가 넘치도록 풍성하게 임했는지를 표현하는 매우 강력한 표현이다. 바울은 자신을 향한 주의 은혜가 너무 커서 도저히 표현하거나 측량할 수 없다는 점을 드러내는 것이다.

이 넘치도록 풍성하다라는 표현이 한글 성경에서는 맨 나중에 위치하지만 헬라어 원문에서는 맨 앞에 위치하여 강조되고 있다.

바울은 주의 은혜가 그리스도 예수 안에 있는 믿음과 사랑과 함께 넘치도록 풍성하였다라고 고백한다. 바울 신학에 있어서 '은혜는 뿌리요, 믿음과 사랑은 줄기요, 선한 행실들을 구원나무의 열매다'라고 헨드릭슨은 말했다.

15절) 13절에서는 바울이 이전에 얼마나 복음에 적대적이었는지를 이어 14절에서는 그런 바울에게 주님의 은혜가 얼마나 넘치도록 풍성하게 임하였는지를 간증한다. 이어 15절, 16절에서 바울은 주의 긍휼에 초점을 맞추고 있다.

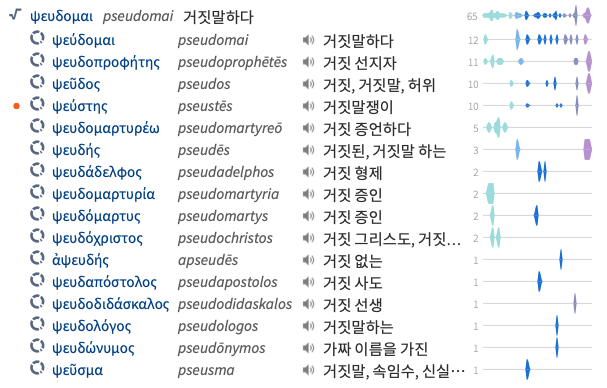

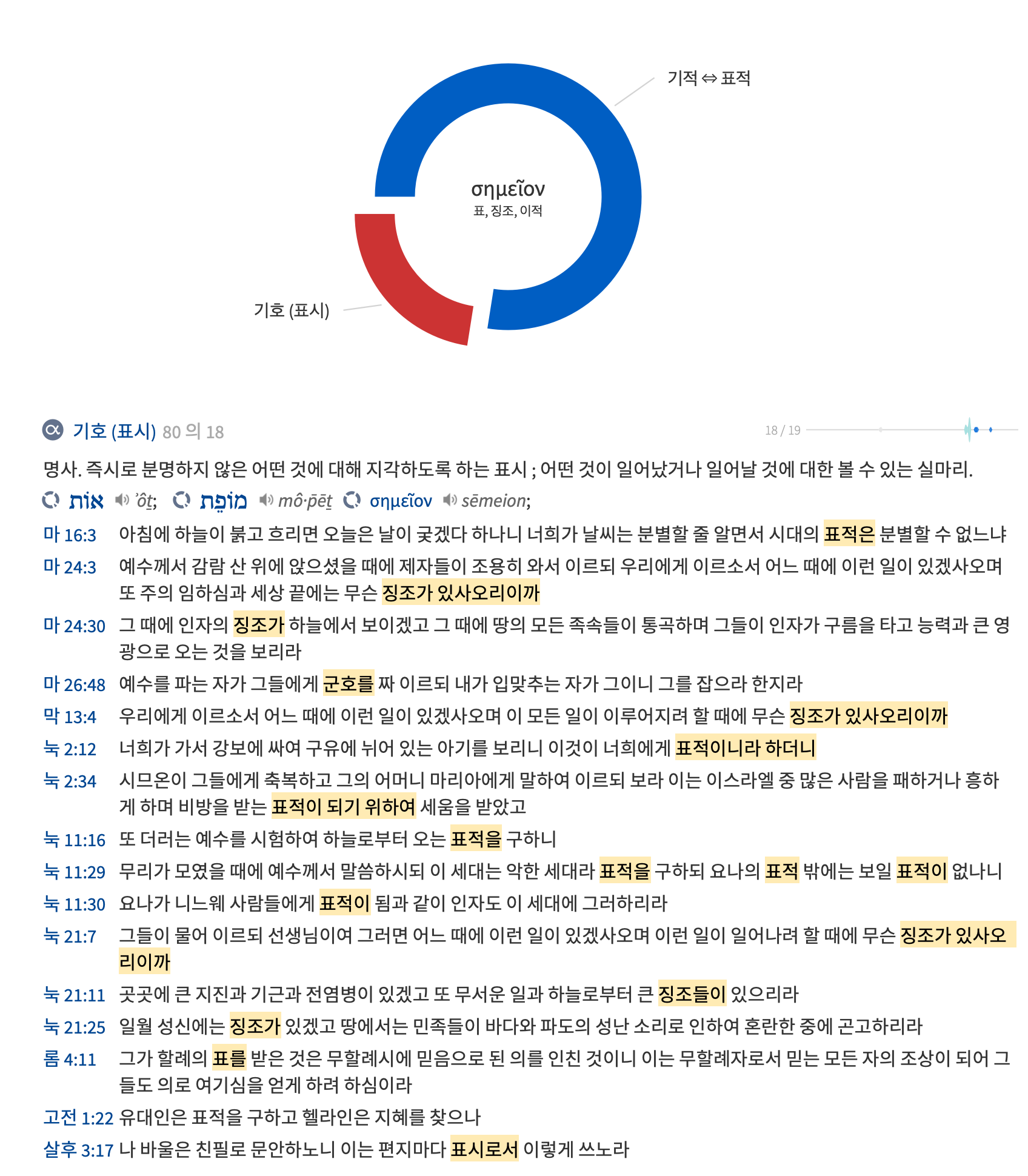

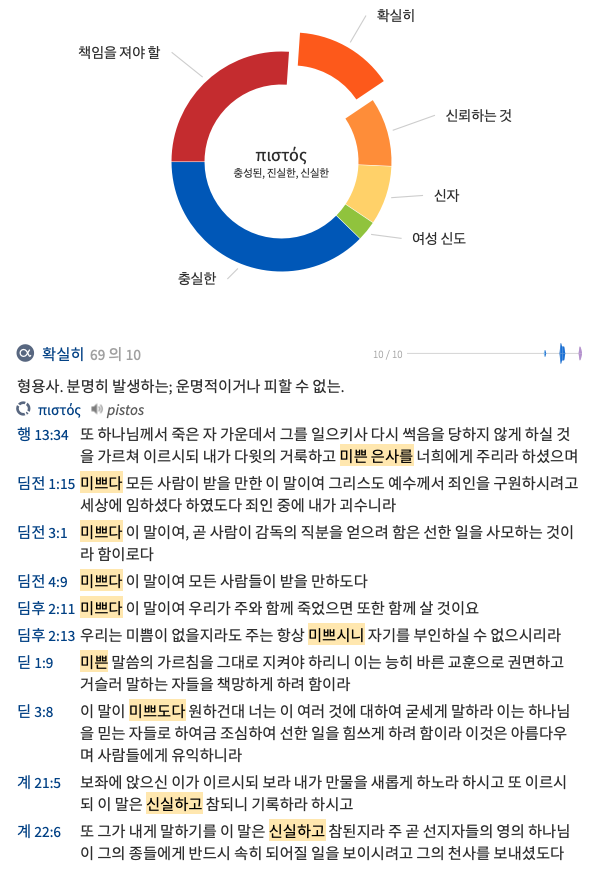

먼저 본문은 ‘미쁘다’(피스토스)라는 표현으로 시작된다. 이는 목회서신의 특별한 특징으로 주위를 환기시키는 표현으로 사용되었다.(3:1, 4:9; 딤후 2:11; 딛 3:8) 특히 목회 서신과 계시록에서는 피스토스와 로고스를 함께 사용하여 말씀의 신실함을 강조하고 있다.

원문의 순서는 ‘피스토스 호 로고스 카이 파세스 아포도케스 악시오스’이다. 이는 ‘미쁘다 이 말이여, 이는 모든 사람이 받을 만하도다’라고 번역할 수 있다. 그렇다면 모든 사람이 받을 만한 미쁘신 말씀은 바로 ‘그리스도 예수께서 죄인을 구원하시려고 세상에 임하셨다’라는 것이다. 이는 요 3:16-17절을 연상시킨다.

요한복음 3:16–17

16하나님이 세상을 이처럼 사랑하사 독생자를 주셨으니 이는 그를 믿는 자마다 멸망하지 않고 영생을 얻게 하려 하심이라

17하나님이 그 아들을 세상에 보내신 것은 세상을 심판하려 하심이 아니요 그로 말미암아 세상이 구원을 받게 하려 하심이라

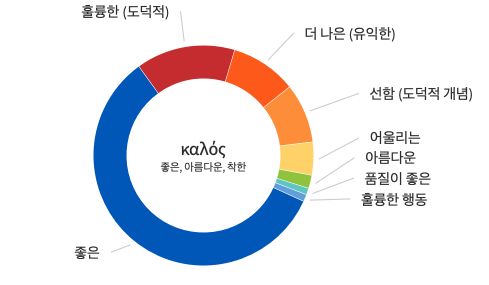

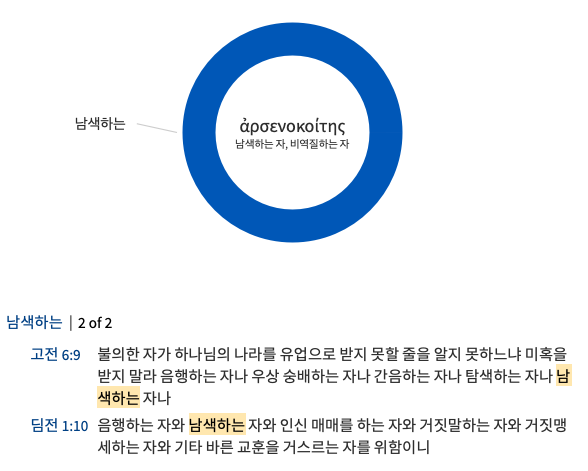

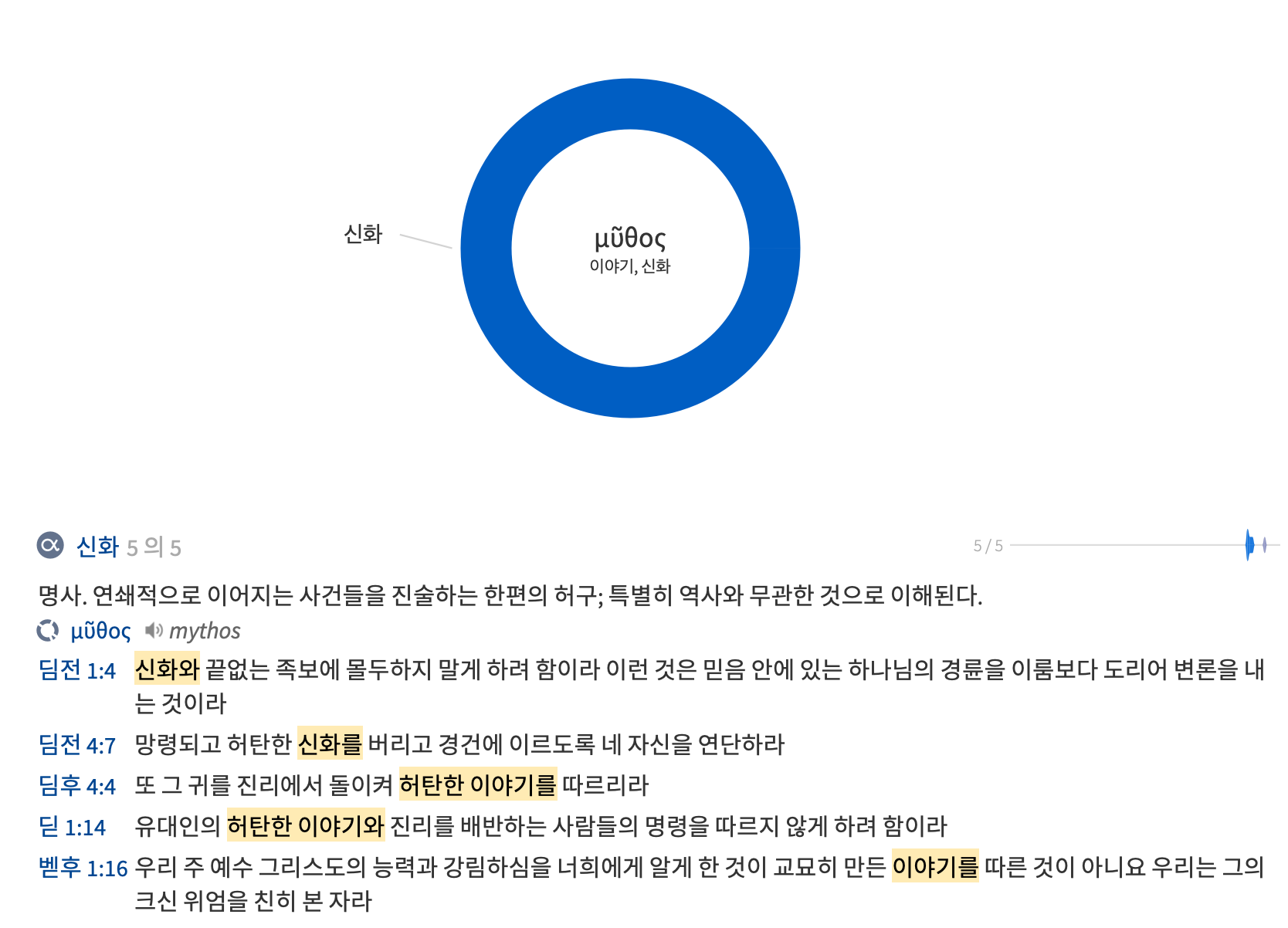

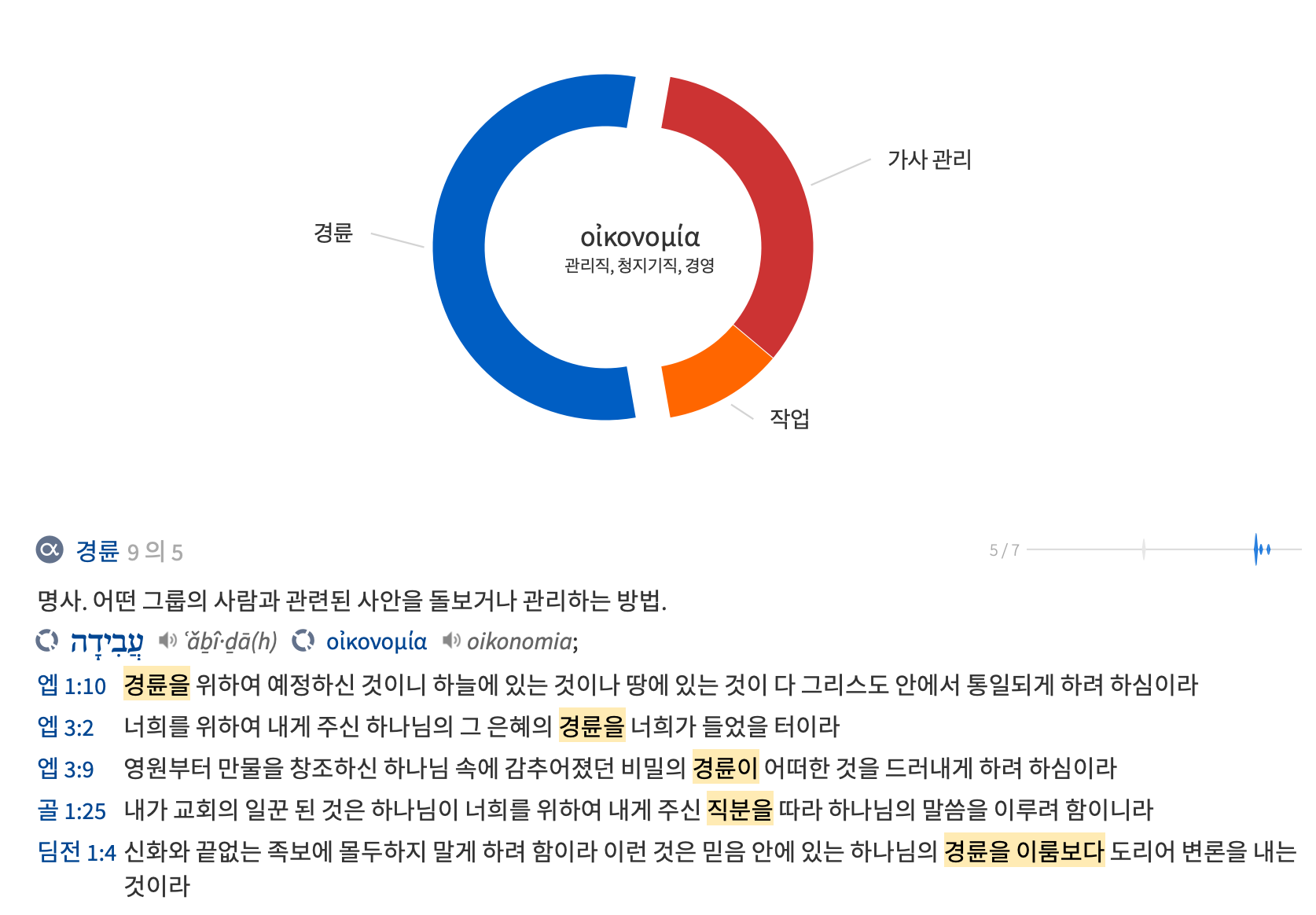

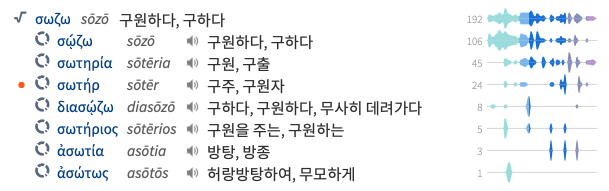

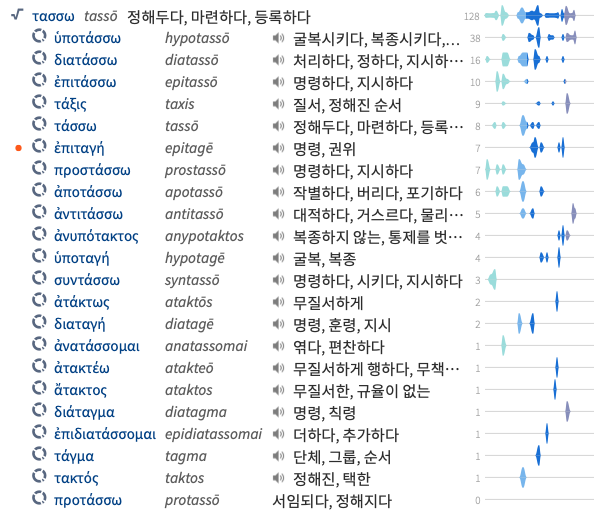

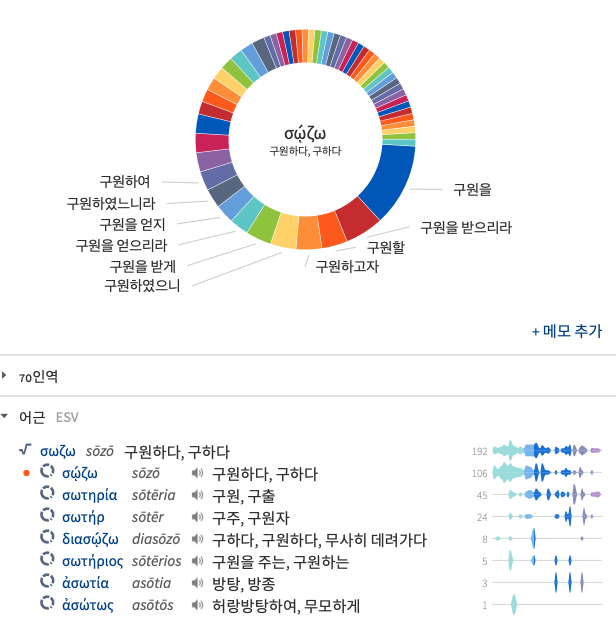

모든 사람이 받을 만한, 모든 사람이 받아야만하는 복음의 핵심을 본절은 밝히고 있다. 그것은 바로 예수께서 무엇을 위해서 이땅에 오셨는지를 밝힌다. 하나님의 아들 예수는 죄인을 구원하시기 위해서 이 땅 가운데 오신 것이다. 본문의 죄인은 ‘하마르톨로스’인데 여기에서 죄악, 불법이라는 ‘하마르티아’가 나왔고 이것의 동사형은 ‘하마르타노’이다. 구원하다는 표현은 헬라어 ‘소조’이다. 이는 구출하다, 구원하다, 치유하다등으로 매우 광범위하게 사용되었다.

바울은 이어서 자신을 설명하면서 ‘죄인중에 내가 괴수니라’라고 말했다. 이는 ‘그리스도 예수께서 세상에 오셔서 구원하시려는 죄인중에 내가 가장 큰 첫째가는 죄인이다’라는 의미이다. 괴수라고 번역된 헬라어는 ‘프로토스’로 이는 ‘처음, 첫째, 으뜸되는’의 의미로 KJV은 이를 ‘chief’ 우두머리라고 번역했고, NIV는 ’the worst’ 최악의로, ESV는 ’the foremost’ 으뜸으로 번역했다. 본절은 바울의 자기 인식을 분명하게 드러낸다. 그는 본절에서 자신을 ‘죄인중의 괴수, 우두머리’로 인식했으며

고린도전서 15:9

9나는 사도 중에 가장 작은 자라 나는 하나님의 교회를 박해하였으므로 사도라 칭함 받기를 감당하지 못할 자니라

에베소서 3:8

8모든 성도 중에 지극히 작은 자보다 더 작은 나에게 이 은혜를 주신 것은 측량할 수 없는 그리스도의 풍성함을 이방인에게 전하게 하시고

사도는 본문에서 ‘에고 에이미’라는 표현을 통해 분명한 자기 인식을 나타낸다. 여기서 ‘에이미’는 1인칭 현재 능동태 직설법 시제로 과거를 회상하는 것이 아니라 지금의 자신의 모습에 대한 고백인 것이다.

이 세가지의 바울의 자기인식을 순서대로 보자면 AD50년 중반의 고린도전서, AD60년 초반의 에베소서, 본서를 AD60중반이라고 본다면 바울은 점점 연륜이 깊어질수록 자신을 향한 하나님의 놀라운 은혜에 비추어볼때 자신이 얼마나 작은 자인지 더 나아가 얼마나 큰 죄인인지를 절감하며 고백했던 것이다. 이러한 고백은 단지 입에 발린 표현이 아니라 하나님의 영광의 복음에 깊이 나아간 겸손한 하나님의 사람들의 공통된 표현이다. 이런 온전한 자기 인식이 있을때에야 비로소 우리는 영광의 복음앞에서 감격할 수 있게 되는 것이다. 스스로 죄인이란 인식이 없다면 죄인을 구원하시기 위해서 이땅가운데 오신 그리스도 예수의 은혜에 대한 감격이나 기쁨도 결코 있을 수 없다.

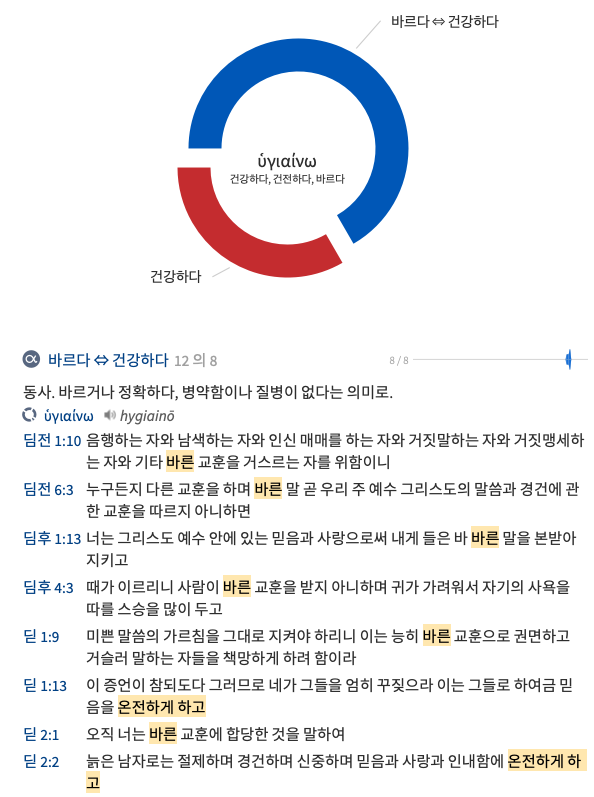

- 1:15 Calling attention to certain sayings as trustworthy is a particular distinctive of the Pastoral Epistles (cf. 3:1; 4:9; 2 Tim. 2:11; Titus 3:8). Christ Jesus came … to save sinners, of whom I am the foremost (cf. Luke 19:10). Paul cannot mean that he now sins more than anyone in the world, for he elsewhere says that he has lived before God with a clear conscience (Acts 23:1; 24:16), and he asks other believers to follow his example (see note on Phil. 3:17). Apparently he means that his previous persecution of the church (1 Tim. 1:13; cf. 1 Cor. 15:9–10) made him the foremost sinner, for it did the most to hinder others from coming to faith (cf. 1 Thess. 2:15–16). Yet it also allowed God to save Paul as an “example” of grace (1 Tim. 1:16). Another interpretation is that, in light of the Holy Spirit’s powerful conviction in his heart, and his nearness to God, Paul could not imagine anyone being a “worse” sinner than he. Godly people with some self-knowledge are prone to think of themselves in this way.

Crossway Bibles, The ESV Study Bible (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2008), 2326.

- Excursus: The “Trustworthy Saying” Formula

The formula occurs five times in these letters. The core phrase is πιστὸς ὁ λόγος (“the saying is trustworthy”), which occurs without expansion in 1 Tim 3:1; 2 Tim 2:11; Titus 3:8. The expanded form πιστὸς ὁ λόγος καὶ πάσης ἀποδοχῆς ἄξιος (“the saying is trustworthy and deserving of full acceptance”) occurs in 1 Tim 1:15 and 4:9. The expansion phrase serves as reinforcement, stressing the need to affirm as true the cited material when (perhaps) the material did not elicit this affirmation clearly on its own (Knight, Faithful Sayings, 29, 144).

In the Hellenistic world, the phrase is attested in Dionysius of Halicarnassensis (Roman Antiquities 3.23.17; 7.66.2) and Dio Chrysostum (Oration 45.3; see further Spicq, 277) and serves the same basic purpose of affirming its referent but it does not appear to be formulaic as such (but see Quinn, 230–32). The only Jewish parallel reported (“The Book of Mysteries” = 1Q27 1:8; see discussion in Nauck, “Herkunft,” 50) is no more than a parallel. This leaves the occurrences in the letters to coworkers as the first “formulaic” use (Marshall, 327). For some the origin of the phrase has been thought to rest in the similar description of God as faithful: πιστὸς ὁ θεός (1 Cor 1:9; 10:13; 2 Cor 1:18; cf. 1 Thess 5:24; 2 Thess 3:3; Heb 10:23; cf. Fee, 52). While the trustworthiness of the “saying” in each context surely owes to its divine origin, that factor would seem to be somewhat farther back in Paul’s thinking and the desire to continue to draw the line between the sound teaching encapsulated by the sayings and the false teaching by means of the πίστις word group more to the fore (cf. Schlarb, Die Gesunde Lehre, 214).

Both the direction and extent of the “sayings” referred to by the formula in 1 Tim 3:1 and 4:9 are disputed (see further the commentary on each text). Most are agreed that in 1 Tim 1:15 and 2 Tim 2:11 the formula precedes the saying and that in Titus 3:8 it follows, but the extent of material encompassed by the formula in the case of Titus 3 (vv. 3–7; 4–7; 5–7, or 5–6?) is debated. It is not clear that the formula uniformly refers to salvation texts, or, indeed, that this should be the criterion for determining the substance of the logos in question (pace e.g. Campbell, “Faithful Sayings”; Young, Theology, 56–57; Johnson, 203, but cf. 250).

What are “faithful sayings”? The answer to this question revolves around that of the function of the formula. Does it mean to affirm the truthfulness of what is said (Marshall, 328–29; Donelson, Pseudepigraphy, 150–51; Trummer, Paulustradition, 204)? Or does it mark off the material to which it refers as part of the accepted tradition (Dibelius and Conzelmann, 28–29; Brox, 112–14; Spicq, 277; Hanson, 63)? Or is it both of these at once (Knight, Faithful Sayings, 19–20)? The majority considers the affirmation of truthfulness to be most significant, with the application of the material being intended (cf. Roloff, 90). The contents of the saying introduced or concluded by the formula, however, do not appear to be fully explained with the category of “accepted tradition.” Most of the sayings have been formulated, or significantly shaped, for use in their present contexts, so it is unlikely that Paul has drawn on a reservoir of “tradition” in the usual sense. Rather, with the formula, Paul emphasizes the authentic correspondence of the saying and its authority with the apostolic tradition, the (his) gospel, the sound teaching, and so on. From the outset, Paul identifies the problem as a collision of his gospel with an opposing teaching (1:3; 2 Tim 2:14–18; Titus 1:11). And in each community Paul’s gospel had come under heavy fire. The “trustworthy saying” formula is a technique by which Paul, in one motion, rearticulates his gospel (and corresponding aspects of teaching), asserts its authenticity and apostolic authority, and alienates the opposing teaching that, by implication (and this is the polemical significance of the πίστις word group), does not belong to the category denoted by the term πιστός (“trustworthy”).

Philip H. Towner, The Letters to Timothy and Titus, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2006), 143–145.

- The content of the “saying”42 is a gospel statement consisting of a traditional verb and purpose statement: “Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners.”43 The broad appeal of this saying may be seen in the way it resonates in varying degrees with Jesus’ mission statements preserved in both the Synoptic and Johannine traditions:

1 Tim 1:15: Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners.

Luke 19:10: For the Son of Man came to seek and to save what was lost.

Mark 2:17: I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners.

John 18:37: and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth.

Perhaps the strongest affinity is with the saying in Luke 19:10, which shares the verb-infinitive combination “came to save,” but lacks the phrase “into the world.”44 The name, “Christ Jesus,” corresponds to the dominant pattern in this letter (see note 1:1). Mark 2:17 includes the verb “come” and makes reference to “sinners,” but the purpose is expressed differently as “calling.”45 Johannine tradition shows ample use of the phrase “into the world” in combination with the verb “to come” (9:39; 11:27; 12:46; 16:28; 18:37; cf. 1 John 4:9),46 but the salvific purpose statement found here is never attached to the Johannine statements, and it is certainly not clear that Paul is indebted to this strand of theology in developing his view of incarnational Christology.47 Clearly, the gospel saying in 1:15 is not a verbatim quote of any text extant to us. Given Paul’s louder echo of Lukan material in 5:18, probably the stronger case can be made for some sort of reworking of the Jesus tradition known to Luke. But whatever pre-existing materials Paul drew on, he has fashioned a new statement, continuous with existing tradition, which exceeds it by placing the salvation work of Christ Jesus into historical relief as a divine work carried out in the human context. Let’s explore this claim further.

42 Gk. λόγος (3:1; 4:5, 6, 9, 12; 5:17; 6:3; 2 Tim 1:13; 2:9, 11, 15, 17; 4:2, 15; Titus 1:3, 9; 2:5, 8; 3:8); its use is varied: “saying” (1:15; 3:1; 4:9, etc.); ordinary “speech, conversation” (4:12); “message, teaching, what is to be preached” (Titus 2:8; 2 Tim 2:17; 4:2); “the word of God” as divine revelation (4:5; 2 Tim 2:9; Titus 1:3; 2:5); “words” (in the plural) that represent what has been preached (6:3; 2 Tim 1:13; 4:15). Schlarb, Die gesunde Lehre, 206–229. Cf. G. Kittel, TDNT 4:100–141; H. Ritt, EDNT 2:356–59.

43 Only this faithful saying is introduced by the recitative ὅτι (“that”).

44 Gk. ὅτι Χριστὸς Ἰησοῦς ἦλθεν εἰς τὸν κόσμον ἁμαρτωλοὺς σῶσαι (1 Tim 1:15); ἦηλθεν γὰρ ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου ζητῆσαι καὶ σῶσαι τὸ ἀπολωλός (Luke 19:10). See Kelly, 54; Brox, 111.

45 Mark 2:17: οὐκ ἦλθον καλέσαι δικαίους ἀλλὰ ἁμαρτωλούς.

46 See e.g. John 9:39: εἰς κρίμα ἐγὼ εἰς τὸν κόσμον τοῦτον ἦλθον; see Windisch, “Christologie,” 221–22.

47 See discussion Dibelius and Conzelmann, 29; Roloff, 90–91.

Philip H. Towner, The Letters to Timothy and Titus, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2006), 145–146.

16절) 본절에서 자신이 어떻게 구원을 받았는지, 긍휼을 입게 되었는지를 밝힌다. 그는 율법에 열심이 있던 자로 예수 믿던 이들을 죽이기에 열심을 품었던 자였다. 그랬던 그가 예수 그리스도를 만나자 이제 생명을 바쳐 그리스도를 전하는 복음 전도자가 된 것이다. 이처럼 바울의 회심은 아주 강력한 본, 모델이 된다. 그는 참된 기독교의 복음이 사람을 어떻게 변화시키는지를 보여주는 본이 된다.

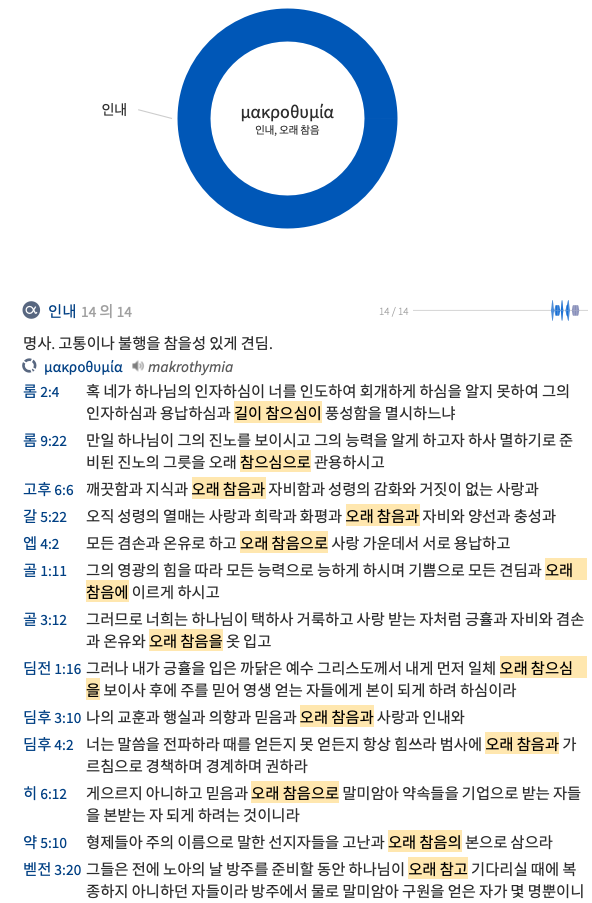

바울은 13절에 이어서 다시금 자신이 긍휼을 입었음을 밝히고 있다. 그는 죄인중의 우두머리, 괴수였다. 그러나 그런 그가 긍휼을 입은 것이다. 그렇게 긍휼을 입은 이유가 바울에게 있는 것이 아니라 오로지 주님의 오래 참으심 때문이었다. 본절에서 ‘오래 참으심’으로 번역된 ‘마크로뒤미안’의 원형 ‘마크로뒤미아’는 ‘길다, 멀다’를 의미하는 형용사 ‘마크로스’와 ‘진노’를 나타내는 명사 ‘뒤모스’의 합성어로 마땅히 심판과 진노를 내려야하는 상황에서 그 진노를 유보하는 것을 의미한다. 이처럼 하나님께서 죄인들에 대해서 인내하시는 것으로 인해 죄인에 대한 용서가 임하게 된 것이다.

바울을 향한 주님의 인내의 목적은 다름 아닌 후에 주를 믿어 영생 얻는 자들에게 본이 되게 하기 위한 것이다. 바울이 본이 될 수 있는 것은 그가 죄인 중의 괴수 였음에도 그리스도의 오래 참으심으로 인해 구원을 받게 되고 하나님의 충성스러운 직분을 받을 수 있다면 그의 뒤를 따르는 이들에게도 용기와 희망이 생기게 되는 것이다. 바울처럼 저렇게 극악하게 율법을 따라 적대적인 삶을 살았던 사람조차도 주님의 오래 참으심의 대상이 된다면 우리들도 마찬가지로 그 오래참으심, 용서와 긍휼의 대상이 될 수 있기 때문이다.

17절) 앞선 12절에서 능력을 주시고 충성되이 여기심으로 직분을 맡겨주신 하나님을 찬양했다. 이어 13-14절에서 회심 이전에 비방자요 박해자요 폭행자였던 자신에게 긍휼을 베푸시고 은혜를 넘치도록 주신 것에 감격했다. 이어 15-16절에서 자신을 죄인중의 괴수로 고백하며 이런 자신에게 임한 하나님의 긍휼을 고백했다. 이제 본절은 자신에게 이러한 불가항력적이고 무조건적인 은혜를 베푸신 하나님의 능력과 영광을 찬양한다.

먼저 바울은 하나님을 영원하신 왕이라고 찬양한다. 개역은 이를 ‘만세의 왕이라고 번역했다. 이는 ‘바실레이 톤 아이오논’으로 직역하자면 ‘세대들의 왕’이다. 바울이 세대, ‘아이오논’을 복수로 쓴 것은 현 세대와 장차 올 세대를 양분하는 유대인들 및 당대 헬라 사고를 가진 사람들의 관념과 일치하는 것으로 하나님께서 현 세대와 오는 모든 세대에 왕으로 통치하신다는 의미를 함축한다. 그래서 개역개정의 번역보다는 개역한글의 번역이 더 적합하다. 이 세상의 왕은 시간과 공간의 제한을 받는다. 언제든지 반역이나 죽음으로 통치가 끝날 수 있지만 하나님의 통치는 영원하다.

두번째로 바울은 ‘썩지 아니하고’라고 하나님을 묘사했다. 이는 ‘압다르토’로 이것의 원형은 ‘압다르토스’인데 이는 부정 접두어 ‘아’와 썩어지다, 더럽히다, 악하다, 해롭게 하다, 멸망하다란 의미를 지닌 ‘프데이로’의 합성어로 절대 더럽혀지거나 약해지거나 해롭게 되거너 멸망당하여 업어지지 않는 분으로, 하나님의 불변성과 불멸성을 나타낸다.

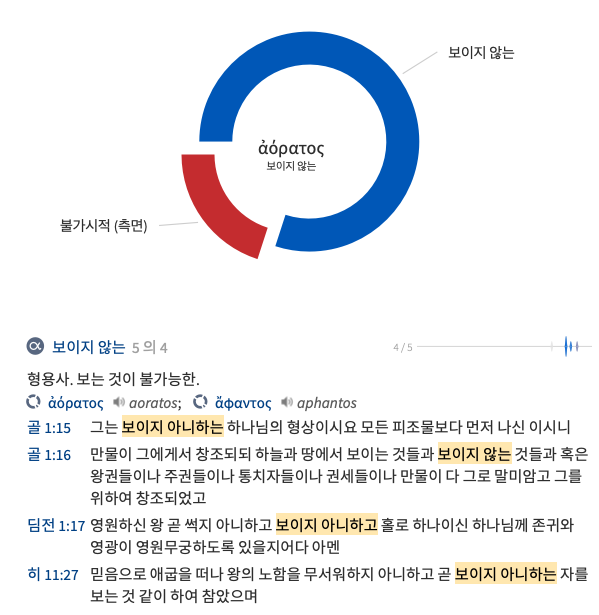

세번째로 바울은 하나님을 보이지 아니하시는 분이라고 표사한다. 이는 ‘아오라토’로 이것의 원형 ‘아오라토스’는 부정 접두어 ‘아’와 보이다란 뜻의 형용사 ‘호라토스’의 합성어로 신약 성경에서 하나님과관련되어 5번 사용되었다. 하나님은 보이지 아니하시는 분이라는 의미는 하나님의 불가견성을 나타냄과 동시에 눈에 보이는 우상과는 완전히 다른 존재이심을 강조하는 것이다. 하나님의 얼굴을 본 자는 없다. 모세조차도 하나님의 영광의 그림자, 뒷모습만 보았을 뿐이다.(출 33:18-23)

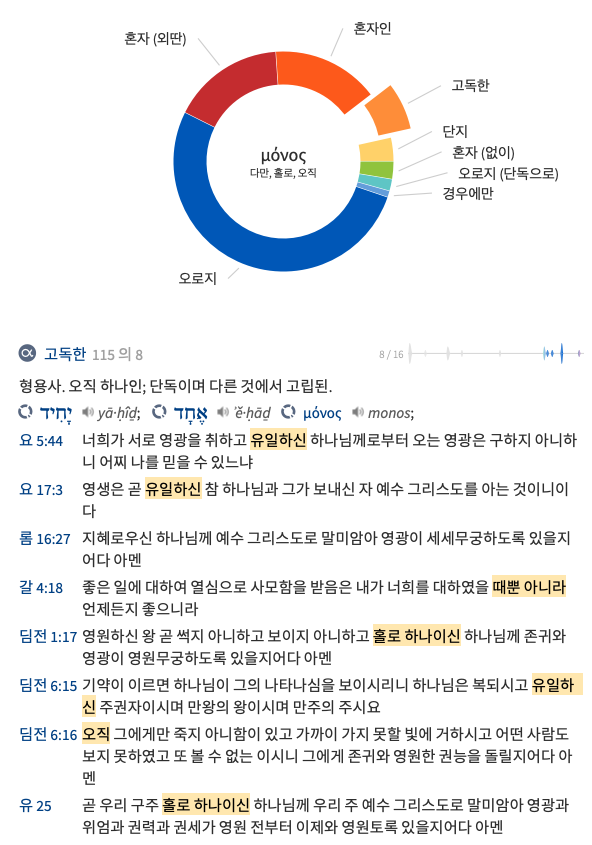

네번째로 바울은 하나님을 홀로 하나이신 분으로 찬양한다. 원문에는 ‘모노’라는 표현이 사용되었는데 이는 오직 하나인, 단독이며 다른 것에서 고립된의 의미이다. 이는 요한복음에서는 ‘유일하신’이라는 표현으로 번역되었다.

바울은 이러한 하나님을 향해서 존귀(티메)와 영광(독사)이 있기를 기원하며 찬양한다. 바울은 기회가 있을때마다 이처럼 하나님을 찬양하는 일을 즐겨했다(롬 11:36; 16:27; 갈 1:5; 엡 3:21; 딤전 6:16). 이어서 본절은 ‘아멘’으로 끝마쳐지는데 이는 ‘네 진실로 그렇습니다. 그렇게 되기를 원합니다’라는 고백이다.

- The next three terms owe their place within Jewish doxological expressions to the Jewish-pagan dialogue. “Immortal,” borrowed from Greek categories by late Jewish writers, in the NT describes God directly only here and in Rom 1:23, where it is clearly shown to be a quality proper to God alone.69 The “invisibility” of God (Col 1:15; Heb 11:27)70 is more widely affirmed in the NT in various constructions. As a quality of God it emerged especially in the polemic of Hellenistic Judaism against the materialistic views of gods in pagan idolatry.71 Equally, the phrase “the only God” (6:16; cf. 2:5) represents a fundamental affirmation of belief that goes back to the Shema of Deut 6:4 (“Hear, O Israel … the Lord is one”) and became standard theology in the early church.72 The original affirmation contested pagan polytheism, which in Deuteronomy was symbolized in Egyptian idolatry, and was later developed and used widely in the running debate with paganism.73 In a purely worship setting, the epithet would draw attention to the supremacy of God.

The expression of praise in the doxology74 comes in the dual phrase “honor and glory” that has become standard in the NT.75 Greek culture had elevated the importance of these elements of good reputation to the highest degree, with the ruler being the epitome of one worthy of such an acclamation. “Honor” is a public acknowledgement of worth.76 “Glory,” in this context, refers similarly to the recognition of honor that is owed to a deserving person of high repute.77 In the set combination, the terms function together to elevate the esteem that is rightly owed to God.78 Accentuating the immensity of honor even more is the prepositional phrase “for ever and ever”79 that forms the standard conclusion to doxologies. Neither the plural form (lit. “for the ages of the ages”) nor the repetition in this longer form reflect precise measurements of time.80 Rather, the Hebrew idiom functions to stretch the praise of the doxology beyond all limits to eternity.81 In the concluding “amen” (6:16; 2 Tim 4:18) the invitation is given to Timothy and the church to join in the acknowledgement.82

69 Gk. ἄφθαρτος; the term only appears late in Jewish writings (Wis 12:1; Philo, Life of Moses 2.171; Unchangeableness of God 26) and was borrowed from Stoic thought (T. Holtz, EDNT 3:422–23).

70 Gk. ἀόρατος; Philo, On Special Laws 1.20; 4:31; On the Cherubim 101 (as an epithet for God after the NT, see PGL, s.v. B.1–2); as a category of things or powers pertaining to God or to the spiritual realm, Rom 1:20; Col 1:16; in 2 Macc 9:5 of an action of God.

71 See esp. Philo, On the Embassy to Gaius 290, 310, 318; On Abraham 75–76; J. Kremer, EDNT 2:528–29; Spicq, 347; the conviction is expressed in various ways (1 Tim 6:16; John 1:18; 5:37; 6:46; 1 John 4:20).

72 Gk. μόνος θεός; Rom 16:27; more widespread in the NT is the similar εἷς θεός formula (Rom 3:29–30; 1 Cor 8:4–6; Gal 3:20; Eph 4:5–6; and discussion at 1 Tim 2:5)

73 2 Macc 7:37; Josephus, Antiquities 8.335; P. Dalbert, Die Theologie der hellenistisch-jüdischen Missionsliteratur unter Ausschluss von Philo und Josephus (Hamburg: Reich, 1954), 124–30.

74 The verb to be supplied is a form of “to be” that fits the implicit request that the items of praise and appellation be acknowledged.

75 Gk. τιμὴ καὶ δόξα; for the combination, see LXX Exod 28:2; Pss 8:6; 95:7; Rev 4:9, 11; 5:13; cf. Heb 2:7, 9; 2 Pet 1:17.

76 Gk. τιμή (“honor, esteem, price, value”; 5:17; 6:1, 16; 2 Tim 2:20); H. Hübner, EDNT 3:357–59; J. Schneider, TDNT 8:169–80.

77 1:11 (see discussion there); 2 Tim 4:18; Titus 2:13 (see discussion). H. Hegermann, EDNT 1:344–48, 345; Thiselton, The First Epistle to the Corinthians, 834–37.

78 Hübner, EDNT 3:358.

79 Gk. εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας τῶν αἰώνων (or the short form, minus the added genitive: εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας); 2 Tim 4:18; Rom 16:27; Gal 1:5; phil 4:20; Heb 13:21; 1 Pet 4:11; 5; 11; Rev 1:6; 5; 13; 7:12.

lit. literally

80 See esp. J. Barr, Biblical Words for Time (Second Ed.; London: SCM, 1969), 67–71.

81 T. Holtz, EDNT 1:44–46, 45.

82 Gk. ἀμήν; in doxologies see LXX Pss 44:14 (MT 41:13); 71:19 (MT 72:19); Isa 25:1; 3 Macc 7:23; 4 Macc 18:24. In NT see Rom 16:27; 2 Cor 1:20; Gal 1:5. See further H. Schlier, TDNT 1:335–38; H.-W. Kuhn, EDNT 1:69–70.

Philip H. Towner, The Letters to Timothy and Titus, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2006), 152–154.

'성경묵상 > 디모데전서' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 딤전 2:1-4 하나님이 원하시는 것 (1) | 2022.09.23 |

|---|---|

| 딤전 1:18-20 믿음과 착한 양심을 가지라 (1) | 2022.09.21 |

| 딤전 1:12-13 비방자, 박해자, 폭행자였던 바울 (0) | 2022.09.13 |

| 딤전 1:8-11 율법의 올바른 사용 (1) | 2022.09.08 |

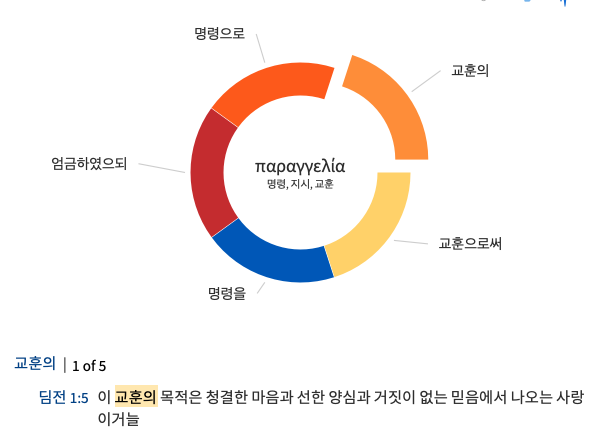

| 딤전 1:4-7 청결한 마음과 선한 양심과 거짓이 없는 믿음 (0) | 2022.09.01 |