10 Now xthere was a famine in the land. So Abram went down to Egypt to sojourn there, for the famine was severe in the land. 11 When he was about to enter Egypt, he said to Sarai his wife, “I know that you are a woman beautiful in appearance, 12 and when the Egyptians see you, they will say, ‘This is his wife.’ Then they ywill kill me, but they will let you live. 13 Say you are my sister, that it may go well with me because of you, and that my life may be spared for your sake.” 14 When Abram entered Egypt, the Egyptians saw that the woman was very beautiful. 15 And when the princes of Pharaoh saw her, they praised her to Pharaoh. And the woman was taken into Pharaoh’s house. 16 And for her sake he dealt well with Abram; and he had sheep, oxen, male donkeys, male servants, female servants, female donkeys, and camels.

17 But the Lord zafflicted Pharaoh and his house with great plagues because of Sarai, Abram’s wife. 18 So Pharaoh called Abram and said, “What is this you have done to me? Why did you not tell me that she was your wife? 19 Why did you say, ‘She is my sister,’ so that I took her for my wife? Now then, here is your wife; take her, and go.” 20 And Pharaoh gave men orders concerning him, and they sent him away with his wife and all that he had.

x ch. 26:1; 43:1

y See ch. 20:1–18; 26:6–11

z 1 Chr. 16:21; Ps. 105:14

The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2016), 창 12:10–20.

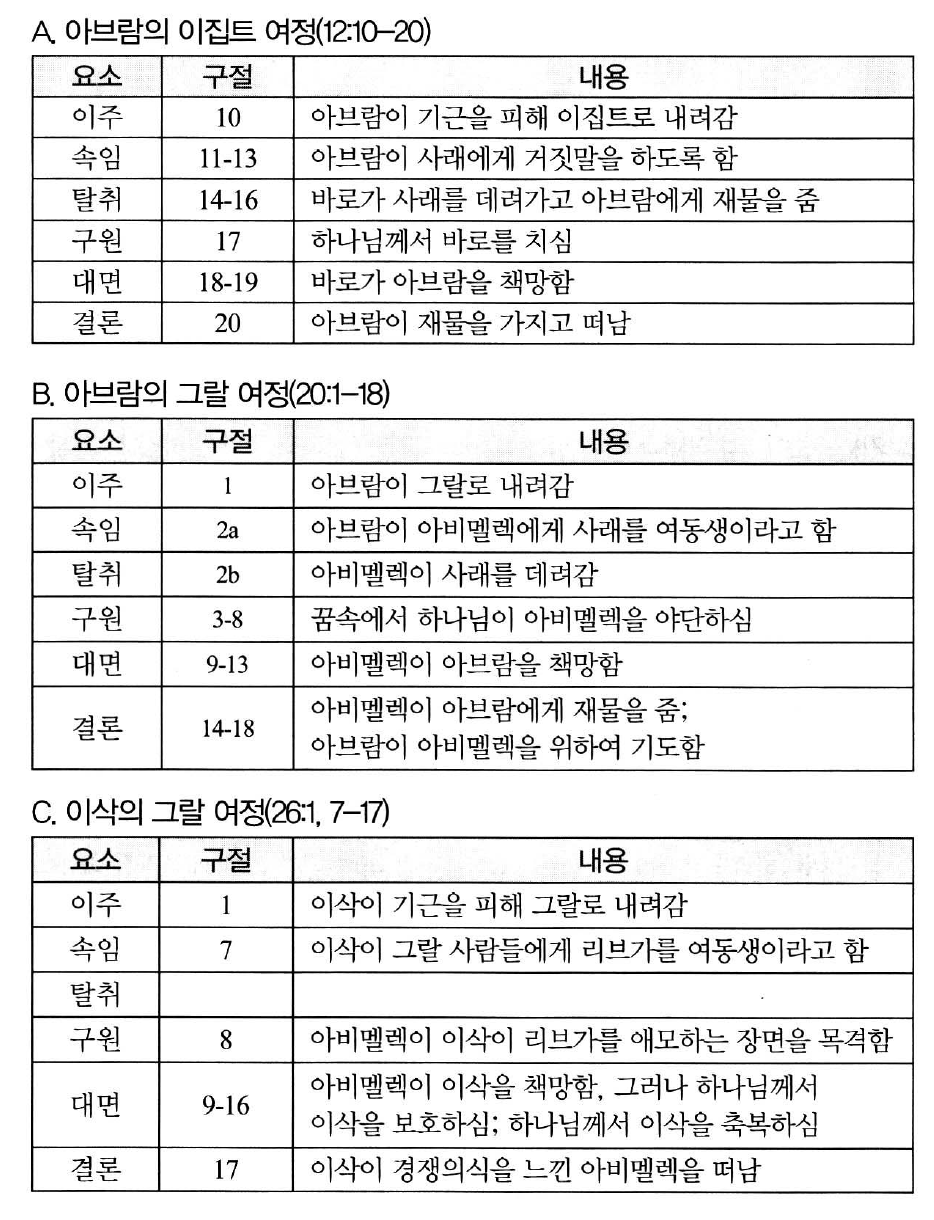

10-13절) 앞서 아브람 일행은 벧엘을 지나 점점 남방으로 내려오고 있었다. 그 땅에 기근이 들어서 아브람이 이 기근을 피하여 애굽으로 이동하였다. 아마도 아브람이 애굽으로 이주할 결심을 한 이유는 애굽, 이집트가 나일강 근처에 위치하여서 다른 지역이 가뭄으로 인해 기근이 심하게 드는 경우에도 음식이 풍족했기 때문일 것이다. 아브람은 애굽에 이르렀을때 자신의 아내 사래에게 당신의 아름다움으로 인해서 애굽 사람들이 나를 죽이고 당신을 아내로 취하게 될지 모르니 자신을 나의 아내라 하지 말고 나의 누이라고 하여 내 목숨을 보존하게 할 것을 요청했다.(12, 20, 26장)

하나님의 말씀에 순종하여 본토 친척 아비집을 떠나 하나님이 명하신 곳으로 이동하는 아브람에게도 아내로 인한 우려와 걱정이 있었다. 하나님께서 자신과 가족을 지키시는 분이심을 온전히 믿지 못하고 아내의 아름다움으로 인해 자신에게 피해가 미칠 것을 두려워하여 자신이 꾀를 내어 거짓말을 하게 한 것이다. 우리는 믿음의 조상 아브라함을 보지만 아브람이 아브라함이 되기까지 수 많은 사건과 사고를 거쳐서 그의 신앙이 이루어지 것이다.

여기서 이해할 수 없는 것은 아브람은 자신의 안전을 위해서 아내인 사래를 희생하는 것처럼 보인다는 것이다. 하나님은 사래를 통해서 아브람에게 자식을 주실 것을 약속하셨는데 아브람은 사래를 위기에 처하도록 한 것이다. 여기서 아브람은 하나님을 두려워한 것이 아니라 사람들을 두려워하고 있었다. 그런데 이 과정에서 하나님께서 역사하심(큰 재앙)으로 아브람과 사래를 보호하셨다.

우리는 왜 성경이 아브람의 윤리적인 잘못에 대해서 구체적으로 기록하고 있는지 알 수 없다. 단지 저자는 이러한 윤리적 문제에 대해서 독자 스스로 판단할 것읋 촉구하는 것이다. 아마도 이스라엘의 원 독자들은 이러한 아브람의 속임수를 통해서 무슨 유익이 있었을지를 알았기에 구체적인 설명이 필요없었을지도 모른다. 이처럼 성경은 이야기를 통해서 우리들에게 많은 것들을 이야기하고 있는데 이 이야기를 처음 받은 이스라엘 백성들은 수많은 위협과 어려움, 심지어 아브람 자신의 도덕적 실수 가운데서도 하나님께서 아브람에게 약속하신 것을 반드시 지키시는 분이심을 깨닫게 되었을 것이다.

실제로 아브람이 자신의 아내 사래를 이복 누이라고 말한 것은 절반의 진실이 담겨 있다.(창 20:12)

- Sarai is instructed to tell any man who confronts her that she is Abram’s sister. This is a half-truth, as 20:12 indicates (although “daughter of my father” could mean adopted daughter).

Scholars debate the proper understanding of Abram’s plan. Why does he think he may come out of this nightmare alive if he can only convince his hosts that the woman traveling with him is his sister? E. A. Speiser suggested that the Nuzi texts provided an answer or a source behind this strange practice.5 A marriage practice among the upper Hurrian classes, and one without counterpart in any other Near Eastern society, allowed a wife to be adopted by her husband as his sister; moreover, a woman given in marriage by her brother (as with Rebekah to Isaac by Laban) would legally become her husband’s sister. Since Abram spent part of his life at Haran (a major Hurrian city), Speiser assumed that it was while he was living in Haran that Abram was exposed to this custom.

5 E. A. Speiser, “The Wife-Sister Motif in the Patriarchal Narratives,” in Biblical and Other Studies, ed. A. Altmann (Cambridge: Harvard University, 1963), pp. 15–28; repr. in Oriental and Biblical Studies, pp. 62–82. See also Speiser, Genesis, pp. xl–xli, 91–94.

Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1–17, The New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990), 381.

당시 사래의 나이는 65세였다. 사래의 아름다움이 어떤 것을 의미한 것일까? 물론 나이가 들어도 소피아 로렌과 같이 아름다운 미모를 잃지 않는 사람들이 있기는 하지만 본문의 아름다움에 지금 우리 시대의 가치와 문화적인 것을 투영할 필요는 없다. 우리의 문화는 관능성과 성적 매력, 외모의 젊음을 아름다움과 직접적으로 연결시키지만 여기에 사용된 아름다움이라는 표현이 창 41:2에서 훌륭한 암소를 묘사하는데도 사용되었다. 따라서 우리는 사래가 젊음의 아름다움을 유지했다고도 볼 수 있고 또한 그녀의 품위와 태도, 표정등이 사람들의 이목을 끌게 했다고 생각할 수도 있다.

당대의 사람들의 수명이 매우 길었기에 65세는 젊은 여성 취급을 받았을 수도 있다.

14-16절) 아브람이 우려한대로 이들이 애굽에 이르렀을 때 애굽 사람들이 그 여인의 아름다움을 보고 바로의 신하들(바로의 왕자들)이 그녀를 보고 바로에게 그녀의 아름다움을 칭찬하였다. 이에 그녀의 아름다움으로 인해 바로가 아브람을 후대하였다. 그래서 아브람이 양과 소와 남수 나귀들과 남녀 노비들과 낙타를 얻었다.

어떤 성경학자들은 창세기에 낙타가 언급되는 것이 시대착오적인 기록이라고 주장한다. 주전 1100년 무렵까지 낙타는 사람들이 이용할 수 있도록 길들여지지 않았다고 주장한다. 하지만 고고학적인 발견을 통해서 이미 주전 3000년 경에 사람들이 낙타를 이용한 것이 발견되기도 하였다. 창세기에는 긴 여행을 할 때나 사막을 지날때 낙타가 언급되는데 이처럼 족장 시대에는 낙타가 흔하지 않았기 때문에 아브람의 부유함을 강조하기 위해서 낙타를 가지고 있었다는 것을 기록한 것이다.

- camels. It is often stated that references to camels in Genesis are anachronistic because camels were not domesticated until the end of the second millennium BC. Archaeological evidence for the early domestication of camels is understandably limited given their use in desert regions. Even in Genesis they are usually mentioned in contexts involving long-distance travel close to deserts (e.g., 24:10–64; 31:17, 34; 37:25). Recent research, however, suggests that people used camels as early as the third millennium BC. Genesis tends to mention them at the very end of lists of possessions (30:43; 32:7), possibly suggesting that they were the least numerous of the animals the patriarchs owned.

e.g. for example

D. A. Carson, ed., NIV Biblical Theology Study Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2018), 45–46.

- Most of the commentary on this verse has focused on the mention of camels as among those animals that Pharaoh gave to Abram. If one accepts that (to the best of our knowledge) camels were not domesticated until much later in the 2nd millennium b.c., then we have here a clear anachronism. W. F. Albright has led the argument most forcibily in this direction.9 He observes the absence of references to camels in the Mari texts, the Amarna Letters, and the Ugaritic texts, all of which have much to say about nomadic peoples. In contrast to ch. 12, ch. 13, where Abram and Lot part company, makes no mention of camels, though flocks or herds are mentioned (13:5). Note, however, that in other events in Abram’s life camels are mentioned, especially in the story of the search for Isaac’s bride-to-be (Gen. 24), which has sixteen references to camels.

Others are not so skeptical about the reliability of the references to camels in Gen. 12.10 For example, a text from Alalakh (18th century b.c.) appears to refer to a domesticated camel.11

9 See, e.g., From the Stone Age to Christianity, 2nd ed. (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1957), pp. 164–65; idem, The Biblical Period from Abraham to Ezra (New York: Harper & Row, 1963), p. 7; idem, Yahweh and the Gods of Canaan (repr. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1978), pp. 62, 156. C. H. Gordon (The Pennsylvania Tradition of Semitics [Atlanta: Scholars, 1986], p. 53) remarks, “he [viz., Albright] abominated camels and adored donkeys. This had a subconscious effect on his pronouncements and publications concerning the patriarchal age. He ‘got rid’ of the camels by turning their very mention in the patriarchal narratives into anachronisms. His love of the donkey impelled him to stress the role of the Fathers as donkey caravaneers.”

10 See J. P. Free, “Abraham’s Camels,” JNES 3 (1944) 187–93; K. A. Kitchen, Ancient Orient and Old Testament (Chicago: Inter-Varsity, 1966), pp. 79–80.

11 See D. J. Wiseman, “Ration Lists from Alalakh VII,” JCS 13 (1959) 29, where text 269:59 reads 1 SA.GAL ANŠE.GAM.MAL, “one (measure of) fodder—camel.” In a following article, “Remarks on the Ration Lists from Alalakh VII,” A. Goetze remarks (p. 37), “This early occurrence of camels, missing in CAD, to be fed and, therefore domesticated, is worthy of special note.” W. G. Lambert (“The Domesticated Camel in the Second Millennium—Evidence from Alalakh and Ugarit,” BASOR 160 [1960] 42–43) objects to the interpretation of Wiseman and Goetze, and suggests that the ideogram in question means “stag,” not “camel.”

Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1–17, The New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990), 383–384.

17-20절) 그러나 여호와께서 아브람의 사래의 일로 바로와 그의 집에 큰 재앙을 내리셨다. 그래서 바로가 아브람을 불러서 네가 어째서 사래가 너의 아내라고 말하지 않았는가? 왜 그녀를 너의 누이라고 해서 나로 하여금 그녀를 내 아내로 삼게 하였느냐라고 물었다. 이제 여기 너의 아내가 있으니 데리고 가라라고 하였다. 그리고 바로가 아브람에 관하여 그의 사람들에게 명령하였다. 그러자 그들이 아브람을 그의 아내와 그의 모든 소유와 함께 보냈다.

하나님께서는 바로가 사래를 자신의 궁으로 불러들이자 그 집에 큰 재앙을 내리신다. 본문을 통해서는 바로가 어떻게 사래가 아브람의 아내인지 알았는지, 또한 어떤 재앙이 내렸는지를 구체적으로 기록하고 있지않다. 단지 하나님께서 이 여인을 취하는 것이 옳은 일이 아님을 깨닫게 하셔서 그녀를 보내게 하셨다.

이러한 죄는 고의, 태만(부주의), 무지로 나눌 수 있다. 첫번째는 자신의 행위가 악함을 알고도 죄를 짓는 행위라면 두번째 태만은 자신이 한 일이 나쁜일임은 알지만 고의로 행하지 않은 경우이다. 세번째 무지는 자기가 한 일이 나쁜일인지 알지 못하고 행한 경우라고 할 수 있다. 여기서 바로의 죄는 세번째에 행한다고 할 수 있다. 사래가 아브람의 아내인지 알지 못했고 그래서 그녀를 아내로 취할려고 했는데 하나님께서 재앙을 내리심으로 잘못을 알려주신 것이다.

우리는 본문을 통해서 애굽의 바로가 비상식적인 폭군이 아니라 매우 정상적인, 도덕적인 왕이었음을 알 수 있다. 당시 왕의 권력이라면 자신이 원하는 것을 얻기 위해서 이에 방해가 되는 이들을 죽일 수도 있었을 것이다.(왕상 21장 나봇의 포도원) 하지만 바로는 그를 죽이지 않고 도리어 조용히 떠나게 하였다. 알 수 없지만 분명히 바로는 아브람의 배후에 어떤 힘이, 하나님의 능력이 있음을 알았고 이로 인해 아브람에게 아내를 데려가고 그의 소유와 함께 떠나 보낸 것이다. 놀라운 것은 바로는 자신이 아브람에게 준 양과 소와 노비나 나귀, 낙타등을 도로 빼앗기 않았다.

본문에 등장하는 기근-체류-포로됨-귀환의 사이클은 이후 출애굽(모세)때에 다시 반복된다. 또한 바벨론으로부터의 포로귀환과도 연관된다. 그런데 출애굽의 귀환과의 차이점을 보자면 본문에서의 애굽은 압제자가 아니었다. 바로는 아브람에게 포악하게 굴지 않았다.

결국 본문속에서 아브람의 계략속에서 하나님께서는 당신의 약속을 이루시기 위해서 개입하신다.

'성경묵상 > 창세기' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 창 13:8-13 무엇을 바라보고 있습니까? (0) | 2020.10.05 |

|---|---|

| 창 13:1-7 아브람의 애굽-네게브-벧엘 여정 (0) | 2020.09.28 |

| 창 12:4-9 하란에서 벧엘에 이르는 아브람의 여정 (0) | 2020.09.22 |

| 창 12:1-3 너는 복이 될지라 (0) | 2020.09.21 |

| 창 11:27-32 데라의 족보 (0) | 2020.09.17 |