728x90

25 iBrothers, pray for us.

26 jGreet all the brothers with a holy kiss.

27 I put you under oath before the Lord to have kthis letter read to all the brothers.

28 lThe grace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with you.

i 2 Thess. 3:1; Heb. 13:18

j See Rom. 16:16

k Col. 4:16

l See Rom. 16:20

The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2016), 살전 5:25–28.

25 형제들아 우리를 위하여 기도하라

26 거룩하게 입맞춤으로 모든 형제에게 문안하라

27 내가 주를 힘입어 너희를 명하노니 모든 형제에게 이 편지를 읽어 주라

28 우리 주 예수 그리스도의 은혜가 너희에게 있을지어다

대한성서공회, 성경전서: 개역개정, 전자책. (서울시 서초구 남부순환로 2569: 대한성서공회, 1998), 살전 5:25–28.

25절) 자신의 선교팀을 위해 중보기도를 부탁하는 바울

형제들아, ‘아델포이’, 주안에서 형제들이기에 서로 멀리 떨어져 있지만 서로를 위해서 기도하는 관계임을 강조한다.

우리를 위하여 기도하라, ‘프로슈케스테 페리 헤몬’, 본문의 기도하라는 표현은 ‘프로슈코마이’이다. 이는 신에게 말하거나 기도를 이야기하다라는 의미이다.

신약에서 기도하다는 동사 ‘유코마이’라는 표현은 7번, 명사인 ‘유케’는 3번 사용되었다. 반면 ‘프로슈코마이’는 85번 사용되었는데 주로 누가복음과 사도행전에서 35번, 마태복음에서 15번, 마가복음에서 10번, 고린도 전서에서 8번 사용되었다. 기도에 해당하는 ‘프로슈케’ 명사는 35번 사용되었다. 반면 요한은 ‘유코마이’라는 표현을 사용하지 않고 예수님의 기도를 일상적인 말을 하는 것으로 표현했다.(요 11:14; 17:1) 요한은 기도라는 직접적인 표현을 사용하지않지만 예수님의 일상이 항상 하늘에 계신 하나님과의 교제의 관계에서의 대화임을 강조하는 것이다. 이는 기도가 특별한 행위를 요구하는 것이 아니라 일상의 삶 전체가 기도라는 것을 강조하는 것이다.

- NT 1 The vb. εὔχομαι occurs only 7× in the NT, usually meaning “to pray” (Acts 26:29; 2 Cor 13:7, 9; Jas 5:16), but on at least one occasion “to wish” (Rom 9:3; poss. also Acts 27:29 and 3 John 2 [cf. BDAG s.v., meaning 2]). The noun εὐχή is used only 3×, meaning both “prayer” (Jas 5:15) and “vow” (Acts 18:18; 21:23).

In contrast, προσεύχομαι occurs c. 85×, esp. in Luke-Acts (35×); it is freq. also in Matthew (15×), Mark (10×), and 1 Corinthians (8×), but is entirely absent from the Johannine writings. It always means “to pray.” The noun προσευχή, “prayer,” is found c. 35×, esp. in Acts (9×; it is lacking in the John’s gospel and letters, as well as in Hebrews, 2 Corinthians, and several other Pauline letters). In one passage this noun is used by metonymy of the place where prayer is made (Acts 16:13, 16). No other compounds are used in the NT

2 The NT teaching on prayer reflects the prior development of the OT. It is modeled, however, upon the praying of Jesus, to which there are repeated references.

(a) As in the OT, prayer is something very personal and specific, a genuine conversation with God. Moreover, since NT believers know God as their Father—with much greater clarity than anything their OT counterparts could have enjoyed—their praying proceeds from a childlike trust, as expressed in the V 2, p 340 typical NT form of address, “Father,” which Jesus taught his disciples to use (Matt 6:6–9; Luke 11:2; cf. Rom 8:15; Gal 4:6; Eph 3:14–15; see ἀββά G5).

(b) The suppliant’s assurance that prayers are heard by God is even stronger in the NT than in the OT, being grounded in an experience of God’s fatherly love in Jesus Christ. Jesus explicitly strengthens this assurance, which comes from faith, by promising that the prayer will be heard (e.g., Mark 11:24). Experiences that appear to be contrary must not tempt us to doubt his fatherly love or the power of prayer (cf. Jesus in Gethsemane, Matt 26:36–46 par., where Jesus’ passion is the Father’s will).

(c) True prayer has great power. It expresses that faith whereby the sinner is justified (Luke 18:10, 14). It is answered with the gift of the Holy Spirit (11:13). It clarifies the way ahead (Mark 1:35–39). It enables the suppliant to receive and put on the whole armor of God (cf. Eph 6:18). Paul encouraged the believer to desire spiritual gifts (1 Cor 14:1). It is necessary to surround all activities with prayer, esp. for the perseverance of the saints and for bold and faithful witness (Eph 6:17–20). True prayer overcomes anxieties (Phil 4:6); but at the same time it is a fight with the powers of evil and of darkness (Rom 15:30; Col 4:12; cf. Matt 6:13). Like the OT, the NT also warns of hindrances that can make prayer ineffectual: licentiousness and lovelessness (Jas 4:3; 1 Pet 3:7); unbelief and doubt (Jas 1:5–7); and an unforgiving spirit (Matt 5:23–24; Mark 11:25).

(d) NT prayer can be about anything, from the smallest matter to the greatest, from the affairs of today to those of eternity. The best example of this is the Lord’s Prayer (Matt 6:9–13 and Luke 11:2–4). Here the prayer for daily bread, which incl. all our other daily needs, is flanked on the one side by prayer for the coming of God’s kingdom and for his will to be done on earth, and on the other by prayer for the forgiveness of sin, for preservation in temptation, and for deliverance from evil. It is, however, not without significance that the prayers that refer to God, his will, his kingdom, and his name stand first. The Lord’s Prayer is embedded in longer discourses concerning true prayer (Matt 6:5–15; Luke 11:1–13); it must be marked by simplicity, concentration, discipline, patient confidence, and obedience. (See E. Lohmeyer, The Lord’s Prayer [1965]; J. Jeremias, The Prayers of Jesus [1967]; B. Young, The Jewish Background to the Lord’s Prayer [1984]; N. Ayo, The Lord’s Prayer: A Survey Theological and Literary [1992]; F. Neugebauer, Das Vaterunser: Eine theologische Deutung, 2nd ed. [2008].)

(e) In addition to supplication, there are, as in the OT, two other main types of prayer: intercession, the efficacy of which is emphasized esp. by Paul and James (Rom 15:30; 1 Thess 5:25; 2 Thess 3:1; Jas 5:14–18; even our enemies should be included, Matt 5:44); and the prayer of praise and thanksgiving and adoration, which is addressed exclusively to God himself, quite apart from his gifts whether earthly or spiritual (cf. esp. Rev 4:8–11; 5:8–14; 7:9–17; et al.). The NT insists that prayer should be constant (e.g., Acts 12:5; 1 Pet 1:22). This amounts to saying that the Christian ought always to live in the presence of the Lord and in converse with him, and constantly to be looking to him (Col 4:2 et al.).

V 2, p 341 (f) Communal prayer seems to have been customary in the early church, both in public worship (1 Cor 11:4–5; 14:13–16:24) and in smaller gatherings (Matt 18:19; Acts 2:46–47; 12:12), though private communing with God is the fountain head of prayer in general (Matt 6:6; 14:23; Mark 1:35; Luke 5:16; 6:12; 9:18). The posture in prayer was either kneeling (Acts 21:5; Eph 3:14), in which case the forehead might touch the ground (Matt 26:39), or standing (Mark 11:15; Luke 18:11, 13), sometimes with uplifted hands (1 Tim 2:8).

3 Individual NT writers show distinctive concerns regarding prayer.

(a) The freq. use of προσεύχομαι in the Lukan writings is striking. For Luke prayer is a basic expression of Christian faith and life, and Jesus shows us how to pray aright (Luke 11:1). Important events in the life of Jesus are marked by prayer to God, and the vital decisions of his apostles and the church are made with prayer (3:21–22; 6:12–13; 9:18, 28–29; 22:44; 23:34; Acts 1:14, 24–25; 6:6; 9:11; 10:9; 13:3). Prayer was experienced as genuine conversation with God, as is esp. clear from those instances when believers are said to receive definite divine instructions (e.g., Acts 10:9–16, 30–32; 13:2).

(b) Although John does not use the εὔχομαι word group, he does refer to Christ’s prayers with the ordinary words for speaking, qualifying them only by saying that Jesus lifted up his eyes to heaven (John 11:14; 17:1). Moreover, it is noticeable that Jesus almost always speaks to his heavenly Father in the immediate situation, i.e., in full view of others and without retiring expressly for prayer (cf. esp. 12:27–28). In this way John indicates Jesus’ continual fellowship with God; in his case praying did not require a special act, since his whole life was one of prayer. His unique relationship to God is emphasized by the fact that he is not described as praying in company with his disciples.

(c) Paul attaches special importance to the fact that true prayer is wrought by the Spirit: “In the same way, the Spirit helps us in our weakness. We do not know what we ought to pray for [τί προσευξόμεθα], but the Spirit himself intercedes for us through wordless groans” (Rom 8:26; see πνεῦμα G4460). In two other relevant passages, Rom 8:15 and Gal 4:6, the apostle uses a different vb., κράζω G3189, “to cry aloud,” in order to express the freedom, joy, and confidence in prayer that spring from our awareness of being God’s children. In other words, such prayer does not originate in any power possessed by us and thus can never be considered as a meritorious work.

Elsewhere Paul urges his readers to “pray [προσευχόμενοι] in the Spirit on all occasions with all kinds of prayers and requests [διὰ πάσης προσευχῆς καὶ δεήσεως]” (Eph 6:18). Prayer is ultimately the indwelling, energizing Spirit speaking with God himself, for “the Lord is the Spirit” (2 Cor 3:17; cf. John 4:23–24; Rom 8:14). Thus prayer is not dependent for its efficacy on human eloquence or on any partic. frame of mind. The apostle emphasizes rather that assurance of salvation is both evidenced and increased by Spirit-wrought prayer (Rom 8:15–16). A sim. idea is expressed when he speaks of his thanksgiving being offered V 2, p 342 “through Christ” (1:8; 7:25). Paul also refers to a kind of Spirit-filled prayer that transcends the limitations of human speech and understanding: the so-called speaking in tongues or praying in the Spirit (1 Cor 14:14–16), though he places greater value on prayer that is intelligible to the hearers (14:19).

(d) According to Jas 5:13, a Christian’s whole life, the good times as well as the bad, should be lived in an atmosphere of prayer; as we bring before God everything that happens to us, each new experience becomes suffused with prayer. Then in the verses that follow (5:14–16) we read that in cases of sickness prayer is to be accompanied by the laying on of hands (implied in the phrase “pray over him”), anointing with oil, and confession of sins. Here the outward actions are considered to be tangible, readily intelligible expressions of prayer for the benefit of the sick individual, while confession of sins is made in order to remove any hindrances to prayer. Finally, we are assured that God answers prayer through the illustration of Elijah’s life (5:17–18).

4 We may conclude this art. with a brief discussion of the semantic relationship between the εὔχομαι word group and other terms associated with prayer. Trench, in a generally helpful treatment of seven relevant nouns (Synonyms, 188–92), suggests that προσευχή, being always used with ref. to God, is “res sacra,” whereas “δέησις has no such restriction”; thus the former term corresponds to Eng. “prayer” and the latter to “petition” (p. 189). The point is well taken insofar as δέησις is used widely by secular authors in a general sense; we should keep in mind, however, that this term is found exclusively in the NT (and almost exclusively in the LXX) in connection with prayer (see δέομαι G1289). The broad meaning “petition, request” is even clearer in the case of αἴτημα G161 (see αἰτέω G160; cf. also ἐρωτάω G2263). Another noun, ἔντευξις G1950, has a general background too, though both of its ocurrences in the NT, as well as most NT uses of its cognate ἐντυγχάνω G1961, suggest that in Christian circles this word group may have taken on a religious sense (Trench’s view [p. 190] that ἔτευξις indicates “free familiar prayer” depends on etym. considerations and is prob. misleading). Finally, ἱκετηρία G2656, which has a picturesque history (referring orig. to an olive branch used as a symbol of humility by suppliants), appears to have the strong sense “earnest entreaty” in its only NT occurrence (Heb 5:7).

Several additional vbs. enter this semantic field as well (see concepts Cry; Prayer). Moreover, various other terms are closely associated with prayer, such as αἰνέω G140, “to praise,” and εὐχαριστέω G2373, “to thank” (see concept Bless).

NT New Testament

vb. verb

NT New Testament

poss. possible, possibly

cf. confer (compare)

BDAG W. Bauer, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, 3rd ed., rev. F. W. Danker (2000)

s.v. sub verbo (under the word)

c. circa (about, around)

esp. especially

freq. frequent(ly)

c. circa (about, around)

esp. especially

NT New Testament

NT New Testament

OT Old Testament

OT Old Testament

NT New Testament

OT Old Testament

NT New Testament

cf. confer (compare)

NT New Testament

OT Old Testament

e.g. exempli gratia (for example)

cf. confer (compare)

par. (and) parallel(s)

cf. confer (compare)

esp. especially

cf. confer (compare)

OT Old Testament

NT New Testament

NT New Testament

incl. include(d)/including

ed. edition(s)

OT Old Testament

esp. especially

cf. confer (compare)

esp. especially

et al. et alii (and others)

NT New Testament

e.g. exempli gratia (for example)

et al. et alii (and others)

NT New Testament

freq. frequent(ly)

esp. especially

e.g. exempli gratia (for example)

i.e. id est (that is)

cf. confer (compare)

esp. especially

vb. verb

cf. confer (compare)

partic. particular(ly)

sim. similar(ly)

art. article

ref. reference

Eng. English

p. page

NT New Testament

LXX Septuagint

cf. confer (compare)

NT New Testament

NT New Testament

Trench R. C. Trench, Synonyms of the New Testament, 9th ed. (1880)

p. page

etym. etymology, etymological(ly)

prob. probable, probably

orig. origin, original(ly)

NT New Testament

vbs. verb(s)

Moisés Silva, ed., New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology and Exegesis (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2014), 339–342.

바울은 데살로니가 형제들에게 자신들을 위하여 기도해줄 것을 요청한다. 이는 자신들이 다른 성도들의 기도가 필요하지 않을 정도로 특별한 존재가 아님을 이해하고 있기 때문이다. 사역을 하면서 자신들을 특별하다라고 생각하는 독불장군식의 자세는 온전한 태도라고 볼 수 없다. 이처럼 바울은 자신이 사도로 기도하지만 동시에 자신을 위해서 기도해줄 것을 자주 요청했다.(롬 15:30; 고후 1:11; 엡 6:18-19; 빌 1:19; 골 4:3)

이처럼 성도는 목회자의 사역에 기도로 동참할 수 있다.(롬 15:30)

- Paul requests his readers, ἀδελφοί, προσεύχεσθε [καὶ] περὶ ἡμῶν (“brothers [and sisters], pray for us also”). This was a common request by Paul in his letters (cf. 2 Thes. 3:1–2; Rom. 15:30–32; 2 Cor. 1:11; Col. 4:3–4). Just as Paul and his fellow missionaries interceded on behalf of their converts, they asked to be remembered in prayer by them. This formed a bond of mutual intercession. If καί is accepted as part of the original reading, and the textual evidence is fairly evenly balanced on this, the point becomes all the stronger. Since v. 23 was a wish-prayer on behalf of the Thessalonians, Paul may well be alluding directly to it as an example of his prayer for the community that he would like the Thessalonians to reciprocate.

Charles A. Wanamaker, The Epistles to the Thessalonians: A Commentary on the Greek Text, New International Greek Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 1990), 207.

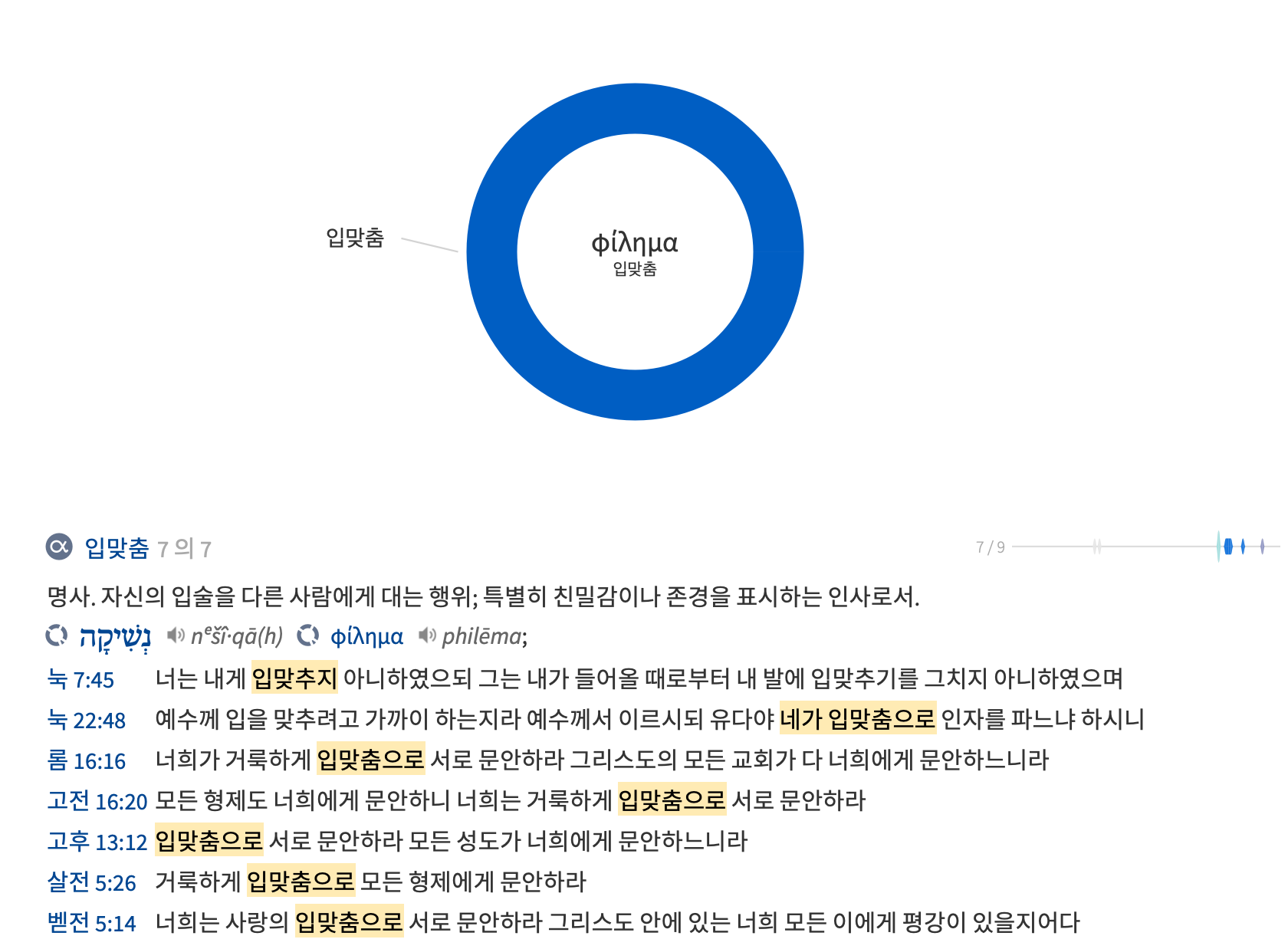

26절) 거룩하게 입맞춤으로(엔 필레마티 하기오) 문안하라(아스파사스데), 본문에 문안하라로 번역된 ‘아스파사스데’ 는 특별히 어떤 사람의 집을 찾아가 문안하는 것이 아니라 사람을 만날 때 일상적으로 인사를 하는 것을 의미한다. ‘하기오’는 ‘거룩한’의 의미이고 ‘필레마티’는 입맞춤을 의미한다. 이것의 원형은 ‘필레마’이다. 이러한 입맞춤은 본래 페르시아인의 인사관습이었는데 이것이 유대로 전해져서 일반적인 인사가 되었다. 이러한 입맞춤은 사랑과 곤경, 화해와 서약을 의미했다. 초대교회는 이를 인사법으로 채용했고(롬 16:16; 고전 16:20; 고후 13:12; 벧전 5:14) 성찬식에서는 예배 의식중 한가지 순서로 시행되었다. 그리스도인들은 예배가 끝난 직후 서로 입을 맞추고 성찬식을 거행했다. 성찬식이 그리스도와 한 몸임을 확인하는 의식이라면 그에 앞서 행해지는 성도간의 입맞춤은 그리스도안에 있는 성도들간의 일치를 의미하는 의식이었다. 따라서 교회 안에서의 입맞춤은 세속 사회의 입맞춤과는 다른 깊은 의미가 담겨 있었다. 그래서 본문에서 바울은 ‘거룩한 입맞춤’이라고 말한 것이다. 그런데 이는 동성만이 아니라 이성간에도 이루어졌는데, 이는 시간이 지남에 따라 세속 이방인들의 비판을 받게 되었고 이로 인해서 알렉산드리아의 클레멘트는 교회안에서 입맞춤하는 것을 공식적으로 금지하였다. 3세기 터툴리안은 ‘아니 도대체 누가 자기의 아내가 형제들 중 아무라도 만나서 서로 밉맞추는 것을 허용하겠는가?’라고 말하며 이를 적극 반대했다. 오늘날 이 명령은 서로 악수를 하는 것으로 대체할 수 있을 것이다.

- holy kiss. The greeting kiss in the ancient world expressed not merely friendship but also reconciliation and unity (Gen 33:4; 45:15; 2 Sam 14:33; Luke 15:20). Paul’s command, therefore, may have in view internal tension in the church (see note on v. 13) and challenges the Thessalonians to remove any hostility.

v. verse in the chapter being commented on

Douglas J. Moo, “The Letters and Revelation,” in NIV Biblical Theology Study Bible, ed. D. A. Carson (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2018), 2157.

- The kiss in the ancient world had a variety of functions both within the family and outside it. Kisses were used to indicate love, respect, reconciliation, even the striking of a contract. They also played various roles in pagan cults (see G. Stählin, TDNT IX, 119–127). That Paul speaks of kissing all the brothers (probably kissing of the opposite sex was not encouraged—see Apostolic Constitutions 2.57.17 for evidence from the fourth century that probably reflects the practice from a much earlier time) suggests that the act had a family connotation for him. The community was part of the one family of God.

That the kiss was to be ἁγίος (“holy”) indicates that it was of religious significance and may point to a setting in the liturgical life of the community (Stählin, op. cit., 139f.), possibly the Eucharist, as Bruce (133f.) suggests. Bruce points out that Justin Martyr (ca. AD 150) speaks of the exchange of a kiss during the eucharistic part of the service. He also borrows from Marshall (145) to show that 1 Cor. 16:20–22 seems to presuppose that a kiss was given as a holy greeting at the time of the Eucharist in the Pauline churches. On the strength of this he suggests that Paul may have intended the letter to be read at the eucharistic meal of the community. Although our knowledge concerning the liturgical practices of the Pauline communities is not extensive, Bruce’s suggestion is plausible, especially because Paul insisted that the letter be read to all the members of the church (v. 27), and the eucharistic service was probably one of the best opportunities for this to happen. Whatever may be the case with this suggestion, the holy kiss served to symbolize the unity of the community as the family of God.

TDNT Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, ed. Gerhard Kittel and Gerhard Friedrich; tr. Geoffrey W. Bromiley. Ten volumes; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1964–76.

Charles A. Wanamaker, The Epistles to the Thessalonians: A Commentary on the Greek Text, New International Greek Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 1990), 208.

27절) 원문에서는 명하다라는 표현인 ‘에노르키조’가 맨 처음 사용된다. 이는 이는 1인칭 단수 동사로 본 서신의 저자가 바울 자신임을 보여준다. ‘에노르키조’라는 표현은 여기 단 한번 사용된 동사로 하나님을 증인으로 하여 누군가에게 엄숙한 의무나 권위적으로 약속, 책임을 지우는 것을 의미하는데 이에 대한 불이행은 처벌로 이루어질 것을 암시한다. 바울은 이를 명하면서 ‘주를 힘입어’(톤 퀴리온’ 하고 있다. 이는 이 맹세를 명하는 자나 듣는 자에 대해서 주님이 증인이 되신다는 사실을 강조하는 것이다. 이를 다시 번역하면 ‘내가 주님으로 말미암아 너희에게 엄명하노니’이다. 그래서 ESV나 NIV는 이를 ‘주님앞에서, before the Lord’로 번역하였다.

바울이 엄히 명하고 있는 내용은 바로 이 편지를 모든 형제에게 읽어 주라는 것이다. ‘읽어 주라’는 ‘아나그노스데나이’로 원형은 ‘아나기노스코’인데 이는 공적으로 크게 읽는 것을 의미한다.(행 13:27; 15:31) 그렇다면 왜 공개적으로 읽으라고 명한 것일까? 이것은 첫번째로 당시 모든 성도들이 성경을 가지고 있지 않았기 때문이다. 두번째로 모든 성도들이 다 글을 읽을 수 있는 것은 아니었기에 문맹인 이들도 하나님의 말씀을 듣고 알게 할 필요가 있었다. 세번째로 하나님의 말씀이 말씀을 전하는 몇몇 이들에게 주어진 것이 아니며 네번째로 당시의 예배에서는 성경이 공개적으로 읽혀졌다는 것을 알 수 있다.

이렇게 공개적으로 낭독된 말씀을 통해서 예배에 참석한 모든이들에게 하나님의 권세있는 말씀이 들려졌고 영향력을 끼쳤음은 주지의 사실이다.

본문의 편지는 ‘에피스톨레’로 공문, 편지, 서신을 의미하는 표현이다.

28절) 우리 주 예수 그리스도의 은혜가 너희에게 있을지어다. 이는 본 서신 전체를 마무리하는 축도의 표현이다. 본 서신의 처음 인사말에 바울은 ‘은혜와 평강’을 구한다. 이제 마지막 인사를 통해서 ‘은혜’를 구하고 있다. 바울의 축도는 삼위 일체의 이름으로 행해지기도 했고(고후 13:13), 본문처럼 주 예수 그리스도, 성자의 이름으로 행해지기도 했으며, 단순히 ‘은혜가 너희에게 있을지어다’(골 4:18; 딤전 6:21; 딤후 4:22)라는 간략한 형태로 행해지기도 했다. 어떤 형태이건 성도들의 영적인 안녕을 기원하는 바울의 마음이 담겨져 있다.

- In characteristic fashion Paul concludes this letter with a benediction. With the exception of 2 Corinthians, which has a more elaborate threefold benediction (cf. 2 Cor. 13:13), and Colossians, which has an attenuated one (Col. 4:18), the benedictions of Pauline letters show only slight variations. Variations occur in how Paul refers to Jesus (“our Lord Jesus” occurs in Rom. 16:20; 1 Cor. 16:23; and “our Lord Jesus Christ” in Gal. 6:18; Phil. 4:23; 2 Thes. 3:18; Phm. 25) and to the recipients of the benediction (the simple form “with you” occurs in Rom. 16:20; 1 Cor. 16:23; “with your spirit” in Phil. 4:23; Phm. 25; the more liturgical expression “with your spirit, brothers [and sisters]; amen” in Gal. 6:18; and “with all of you” in 2 Thes. 3:18).

The benediction here, ἡ χάρις τοῦ κύριου ἡμῶν Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ μεθʼ ὑμῶν (“the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with you”), is identical to that of Rom. 16:20 and 1 Cor. 16:23. The relatively fixed form probably derives from the liturgical language used by Paul and in the Pauline churches, but it reflects the profound theological conception of the early Church that Jesus Christ was the source of divine grace, that is, “the totality of salvation” (H. Conzelmann, TDNT IX, 394), for those who confessed him as Lord.

TDNT Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, ed. Gerhard Kittel and Gerhard Friedrich; tr. Geoffrey W. Bromiley. Ten volumes; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1964–76.

Charles A. Wanamaker, The Epistles to the Thessalonians: A Commentary on the Greek Text, New International Greek Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 1990), 209.

'성경묵상 > 데살로니가전서' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 살전 5장 23-24절 바울의 중보 기도 (1) | 2022.05.26 |

|---|---|

| 살전 5장 19-22절 범사에 헤아려 좋은 것을 취하라 (0) | 2022.05.17 |

| 살전 5장 16-18절 그리스도 예수 안에서 너희를 향하신 하나님의 뜻 (0) | 2022.05.09 |

| 살전 5장 14-15절 형제들에 대한 권면 (0) | 2022.05.04 |

| 살전 5장 12-13절 리더들을 귀히 여기라 (0) | 2022.04.29 |