728x90

5 This is fevidence of the righteous judgment of God, that you may be gconsidered worthy of the kingdom of God, for which you are also suffering

f [Phil. 1:28]

g [Acts 14:22]; See Luke 20:35

The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2016), 살후 1:5.

5 이는 하나님의 공의로운 심판의 표요 너희로 하여금 하나님의 나라에 합당한 자로 여김을 받게 하려 함이니 그 나라를 위하여 너희가 또한 고난을 받느니라

대한성서공회, 성경전서: 개역개정, 전자책. (서울시 서초구 남부순환로 2569: 대한성서공회, 1998), 살후 1:5.

바울은 데살로니가후서를 기록하면서 앞선 인사말 후에 본론 첫부분에 해당하는 오늘 본문을 통해서 하나님의 공의의 심판의 표로서의 성도의 환난을 이야기하고 있다. 이는 이 문제가 그만큼 시급한 것으로 여겨졌기 때문이다.

5절) 원어 자체에는 ‘이는’이 없다. 본절에서 말하는 것은 앞선 4절의 ‘모든 박해와 환난 중에서 나타난 데살로니가 성도들의 인내와 믿음’이다. 바로 이것이 ‘하나님의 공의로운 심판의 표’라고 말하는 것이다. 이런 모든 박해와 환난은 하나님의 나라에 합당한 자로 여김을 받게 하는 표이다. 하나님 나라의 백성은 마땅히 그 나라를 위하여 고난을 받아야 한다.

본문에서 ‘표’로 번역된 ‘엔데이그마’는 증거라는 뜻으로 진실이 규명되거나 반증되는 것으로 추정되는 모든 사실 문제를 규명하는 수단을 의미한다. 말하자면 리트머스 시험지와 같이 이것이 산성인지 염기성인지를 알기 위해서 페톨프탈레인 용액을 떨어뜨리거나 리트머스 시험지에 집어넣어 변화되는 색깔을 관찰하는 것과 같다. 또한 ‘공의로운’에 해당하는 ‘디카이아스’의 원형 ‘디카이오스’는 편벽됨이나 그릇됨이 전혀 없이 옳은 것을 의미한다. 하나님께서는 외모로 취하지 않으시고 심는대로 거두시는 분이시다.(갈 6:7)

성도의 고난이 어떤 의미에서 하나님의 공의로운 심판의 표인가? 하나님의 공의는 믿는 자에게는 구원으로 믿지 않는 자에게는 형벌의 심판으로 임하게 된다. 고난이야말로 믿는 자들이 이 세상속에서 우리의 신앙을 지키고 강화시킬 수 있는 기회가 된다. 마치 사막을 여행하는 여행자가 모래바람과 목마름에 맞서 싸워야 하는 것과 같다. 성도가 고난을 인내와 믿음으로 감당할 수 있는 것은 놀라운 구원의 은혜, 하나님나라의 영광을 알고 이를 소망하기 때문이다. 하나님의 공의로운 심판은 성도들에게는 보상과 구원의 심판이 되는 것이다.

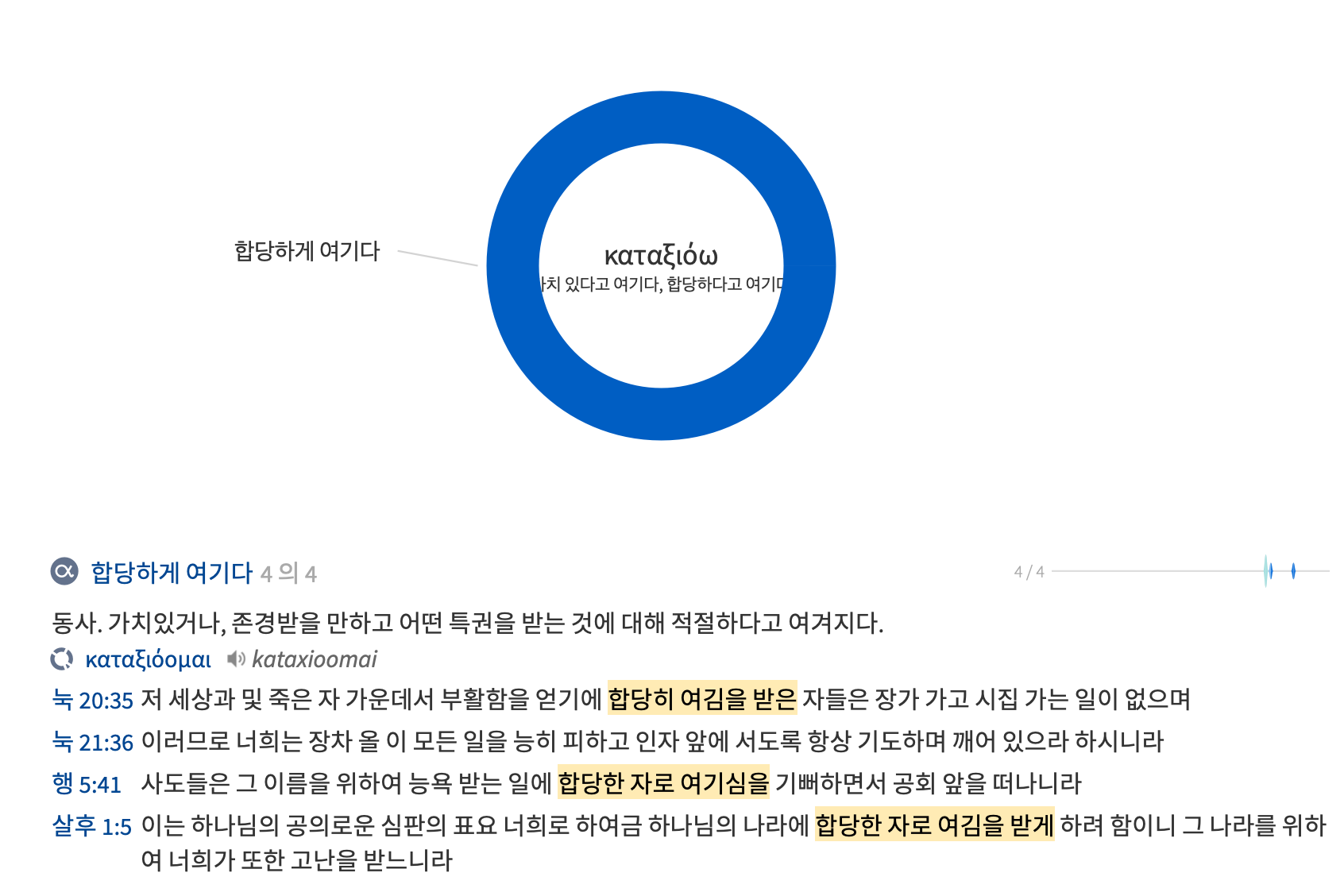

우리 성도들에게 고난을 허락하신 목적은 하나님의 나라에 합당한 자로 여김을 받게 하기 위해서이다. 다른 말로 성도들은 복음으로 인하여 당하는 박해와 환난 가운데서 인내하고 믿음을 지킴으로 인해 하나님 나라에 합당한 자로 여김을 받도록 부르심을 받은 존재들이라는 것이다. 따라서 고난은 하나님의 무관심이 아니라 하나님의 백성이라는 증거가 되는 것이다. 본문에서 ‘합당한 자로 여김을 받게 하다’라는 표현인 ‘카단시오데나이’의 원형 ‘카탁시오오’는 법적 용어로 ‘적합하다고 간주하다. 합당하다고 여기다’라는 의미이다.

본문은 신적 수동태 표현으로, 합당히 여기시는 주체가 바로 하나님이시다. 하나님의 나라는 하나님의 통치와 다스림이 완전히 이루어지는 곳이며 예수님의 재림시에 완성될 곳이다. 고난을 이긴 성도야말로 최후 심판 이후 하나님의 나라에 들어가기에 적합한 자로 여김을 받게 된다는 것이다.

‘고난을 받다’라는 ‘파스케테’는 ‘파스코’의 현재 능동태 직설법 동사로 성도가 이 세상에서 고난을 받는 것이 변치 않는 진리임을 표현하는 것이다. 여기서 말하는 ‘그 나라’는 앞선 ‘하나님의 나라’이다. 성도의 고난은 소극적으로는 하나님나라에 들어가기 위해서 어쩔 수 없이 받아야하는 것이면서 동시에 적극적으로 하나님나라의 영광을 위해서 받아야 하는 것이다. 우리가 하나님나라의 백성으로서 무엇을 위해서 지금 고난을 받고 있는 것인지를 알지 못한다면 그 고난은 우리에게 영광이 될 수 없다. 우리가 받는 고난이 우리를 구원하신 하나님 나라를 위해, 그분을 대적하는 세상속에서 그분을 믿는, 그분을 따르는 백성으로서의 독특한 신앙때문에 일어날수밖에 없는 것임을 알게 될 때 우리는 이를 믿음으로 인내하고 극복할 수 있으며, 고난 가운데 낙심하지 않고 믿음의 역사를 이루어낼 수 있다.

- 히 12:3-11

본문에서 ‘하나님의 공의로운 심판의 표’가 무엇인가에 대해서 여러 학자들이 다양한 견해를 말하고 있다.

1) 데살로니가 성도들의 인내와 믿음

2) 데살로니가 성도들이 당하고 경험하고 있는 박해와 환난

3) 박해와 환난 가운데 그들의 인내와 믿음

- 1:5 The interpretation of this verse is pivotal for a proper understanding of the whole letter. Unfortunately it resists easy explanation. Uncertainty exists concerning the connection of ἔνδειγμα τῆς δικαίας κρίσεως τοῦ θεοῦ (“evidence of the righteous judgment of God”) with its immediate context and the significance of the term ἔνδειγμα (“evidence” or “sign”). Since ἔνδειγμα can be either nominative or accusative, we must either supply ὅ ἐστιν or take ἔνδειγμα as an accusative in apposition. In either case the question arises as to what constitutes the evidence of God’s righteous judgment. There are three possible answers: (1) It is the Thessalonian Christians’ endurance and faith; (2) it is the persecution and affliction that they experience; or (3) it is their endurance and faith in the face of persecution and affliction.

The most common explanation among English-language commentators views the “evidence” as the perseverance of the Thessalonians in spite of persecution and affliction (see, e.g., Frame, 226; Morris, 198; Bruce, 149; Best, 254f. pushes this interpretation further by claiming that even Paul’s boasting is included in the sign). Common to this understanding of the “evidence” is the belief that Phil. 1:28, where ἔνδειγμα (“sign” or “proof”) occurs, offers a basis for explaining 2 Thes. 1:5. According to Phil. 1:28 the fact that the Philippians were not intimidated by those who opposed them was a sign (ἔνδειγμα) of destruction to their opponents but for them it was a sign of their salvation from God. Thus for the Thessalonians the evidence of the righteous judgment of God consisted in their endurance of oppression. Their perseverance would not have been possible without God’s help. Best (255), along with most others holding this view, sees a reference to the eschatological judgment of God, but Marshall (173) urges that the judgment in mind was a process taking place at the time the letter was written.

This whole line of explanation, whether the judgment is seen as a present process or a future one, fails on two scores. First, the grammar does not require us to assume that the “evidence” is the endurance and faithfulness of the Thessalonians in their persecution and affliction. In fact it is more natural to relate it to the words “in all your persecution and the affliction that you suffer” because of the word order in the sentence. The validity of this observation is confirmed by v. 5’s focus only on the suffering of the Thessalonians, not on their perseverance; furthermore, in vv. 6f. the righteous judgment of God is based on the application of the lex talionis to the oppressors, while those who are afflicted are granted relief without emphasis on their endurance (see von Dobschütz, 242). (I shall explore the way in which the suffering of the Thessalonians is understood as evidence for the righteous judgment of God in a moment.)

Second, reference to Phil. 1:28 is of dubious value since the meaning of the sign differs between that text and 2 Thes. 1:5. In the former the sign is proof of salvation for Christians and destruction for their adversaries, while in 2 Thes. 1:5 the sign concerns the righteous judgment of God. Bassler (“Enigmatic Sign,” 499) rightly points out that the righteous judgment of God is not nearly so obviously connected with the endurance of the Thessalonians in the face of persecution as is the Philippians’ salvation with their fearless adherence to the faith. Put slightly differently, it is difficult to conceive in what way the Thessalonians’ perseverance presages the righteous judgment of God without introducing extraneous ideas into the text such as the notion that God has granted the Thessalonians the ability to persevere and remain faithful (see Rigaux, 620).

This observation effectively rules out the first and third possibilities described above for the identification of the “evidence” of God’s righteous judgment. It also points to the second, namely, that the persecution and affliction that the Thessalonians experienced was the evidence referred to by Paul.

The view that the evidence involved the actual persecution and the affliction of the Thessalonians has the support of a number of scholars (e.g., von Dobschütz, 242; Dibelius, 26; Rigaux, 620; Marxsen, 68; Bassler, “Enigmatic Sign,” 500f.). But generally this position has suffered from the inability of those who hold it to explain how tribulation and suffering provide direct evidence for the righteous judgment of God any better than those maintaining the third position described above.

Bassler (op. cit., 501–506), building on the work of Wichmann (Leidenstheologie), has convincingly shown that v. 5 should be understood in terms of a theology of suffering that began to emerge prior to and during the first century AD (cf. Aus, Comfort, 71–75). Four elements played an important role in the theology of suffering, as such texts as Pss. Sol. 13:9–10, 2 Macc. 6:12–16, and 2 Bar. 13:3–10; 78:5 (see also 48:48–50 and 52:5–7) demonstrate (cf. Heb. 12:3–11, which also has strong affinities with a theology of suffering). First, a powerful sense of God’s retributive justice existed; second, present suffering by the pious was explained as chastisement (or atonement) that would make them worthy of future glory; third, the present untroubled position of the godless and their future affliction by God were seen as the reverse of the experience of the pious; and fourth, the present suffering of the elect was accepted as evidence of God’s election and justice. The affinities of 2 Thes. 1:5 and its context with the primary features of the emerging theology of suffering are striking, as Bassler has pointed out. First, vv. 6 and 8f. emphasize the retributive justice of God; second, v. 5 stresses that the suffering of the Thessalonians was intended to make them worthy of the future blessing described as the dominion of God; third, vv. 6f. present a reversal of fortunes when those who afflict others will themselves be repaid by God with affliction and those who are currently afflicted will be granted rest; and fourth, vv. 3f. reveal that the evidence for the righteous judgment of God is the actual suffering of the Thessalonians that has the effect of making them worthy of God’s dominion (cf. Heb. 12:3–11).

Bassler (“Enigmatic Sign,” 507–509) demonstrates that this interpretation has an important consequence for our understanding of the relation between 1:5–12 and 2:1–12. Taking up a suggestion of R. Aus (Comfort, 36), she maintains that 1:5–12 “deal[s] directly with the issue [of persecution] that raised the Day-of-the-Lord question” in 2:1–12 (508). Bassler reconstructs the connection in the following manner. For some reason the community assumed that the day of the Lord had come (or the author thought that they did; 2:2), but their experience of persecution directly contradicted this, calling into question God’s justice since the oppression of the elect should not have persisted after the day of the Lord had arrived. The author of the letter used ideas drawn from the theology of suffering to argue that the persecution of the readers was actually evidence for God’s justice in that it was making them worthy to share in the dominion of God in the future and at the same time he maintained that those who oppressed them would be subject to divine retribution at the time of the parousia (1:6, 8f.; 2:9–12).

Although Bassler’s views concerning the day of the Lord require refinement (see my comments on 2:1), the strength of her interpretation is that it makes better sense of 1:4f. than any other explanation of these problematic verses, and attempts to clarify the inner connection between the affliction of the Thessalonians and the problem created by various claims among them that the day of the Lord had arrived. Thus, as suggested above, the correct understanding of vv. 4f. enables us to interpret more precisely the main thrust of the letter.

The evidence spoken of by Paul involves τῆς δικαίας κρίσεως τοῦ θεοῦ (“the righteous judgment of God”). This can only be a reference to future judgment associated with the day of the Lord. Paul does not bring the judgment into the present on account of his belief in the imminence of the parousia of Christ (cf. 1 Cor. 4:5). The mention of the future retributive justice of God in v. 6 and the compensatory justice of God in v. 7 confirms this interpretation. The prospect of the righteous judgment of God in the near future was integral in maintaining the faith and commitment of new Christians when they encountered opposition from those around them and in the face of the behavioral demands of their new religion.

The clause εἰς τὸ καταξιωθῆναι ὑμᾶς τῆς βασιλείας τοῦ θεοῦ (“that you may be considered worthy of the dominion of God” [on the use of “dominion” for βασιλεία see comments on 1 Thes. 2:12]) may express either purpose or result. Best (255) relates it directly to the preceding phrase “the righteous judgment of God.” It seems much more probable, however, that it refers back to the persecution and affliction mentioned in v. 4. The idea of being considered worthy of the dominion of God is difficult to understand either as the purpose of the righteous judgment of God or as its result without reference to the behavior or experience of the Thessalonians (cf. 1 Thes. 2:12). Also the phrase “the dominion of God” is qualified by the words ὑπὲρ ἧς καὶ πάσχετε (“for which also you suffer”). This directs the reader back to the words “in all your persecutions and afflictions that you bear.” If the εἰς τό clause refers back to the persecution and affliction mentioned in v. 4, then it should be taken as a result clause. It was not necessary for the readers to suffer in order to be considered worthy of God’s dominion, but the writer certainly wished to comfort them with the fact that as a result of their experience of affliction they were considered worthy of it by God (cf. Aus, Comfort, 60).

“The dominion of God” here, as is generally the case in Paul’s letters, alludes to the sphere in which the future salvation of God will be experienced, and, as on a number of occasions, its use is connected with the behavioral or experiential side of the Christian faith (cf. 1 Thes. 2:12; 1 Cor. 6:9f.; Gal. 5:21). The Thessalonians’ suffering resulted from their desire to share in the dominion of God, and hence Paul seeks to reassure them that their suffering will be rewarded (v. 7), while those who inflict suffering on them will in turn suffer (vv. 6, 8f.).

2 Bar. Syriac Apocalypse of Baruch

Charles A. Wanamaker, The Epistles to the Thessalonians: A Commentary on the Greek Text, New International Greek Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 1990), 220–223.

'성경묵상 > 데살로니가후서' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 살후 1장 10-12절 그 부르심에 합당한 자 (0) | 2022.06.22 |

|---|---|

| 살후 1장 6-9절 하나님의 심판의 원칙 (0) | 2022.06.21 |

| 살후 1:3-4 바울의 감사와 자랑 (0) | 2022.06.10 |

| 살후 1:1-2 데살로니가인의 교회 (0) | 2022.06.09 |

| 데살로니가후서 서론 (0) | 2022.06.08 |